It’s Time for a Heritage Tourism Reset

Heritage Tourism has experienced a seismic shift during the pandemic, and now, in the post-pandemic era, there is a rare opportunity to pause and rethink our approach to both heritage and tourism.

As Darren Peacock, CEO of National Trust of South Australia said recently at the 2022 National Trust Conference, “It’s time for a Heritage Tourism reset.”

Heritage and tourism have long been uneasy bedfellows. A longstanding concern regarding tourism is that it can be overwhelming for destinations, especially heritage designations – for example when massive cruise ships full of eager tourists spill out over treasured destinations. Quebec City, a city of 540,000 residents, was receiving a staggering five million visitors per year before Covid-19 struck. The city has been working with residents to manage tourism, including plans to reroute tour buses outside the historic district, and there is more work to be done.

In 2015, UNESCO set Sustainable Development Goals that include tourism. These goals promote the development of quality tourism experiences that encourage responsible behaviour among all players, and the protection of heritage sites around the world.

Since the pandemic, thoughts about tourism are shifting again. Communities have been asking, how can we make tourism work for us? How can we bring our whole community into the heart of the conversation about tourism instead of just calculating how many “heads in beds” these tourists contribute to our local economy?

Subsequently, a more regenerative approach to tourism is gaining traction. ‘Regenerative tourism’ is an approach where the visitor or guest contributes back to the community they are visiting. The term regenerative tourism was pioneered by Anna Pollock, founder of Conscious Travel – a social enterprise whose mission is “to create a flourishing visitor economy that doesn’t cost the earth.” Pollock has been advocating since 1995 for a more holistic and integral approach to tourism that would allow tourists, businesses, communities and ecosystems all to flourish. Regenerative tourism should bring revenue into communities, offer good jobs and protect the local culture.

Regenerative tourism is showing up in places around the world. Here are a few examples.

Giant’s Causeway, Northern Ireland

© Putting the Local in Global Report by the International National Trusts Organisation

As one of Northern Ireland’s most popular destinations, the Giant’s Causeway has experienced longstanding tension between the local community and the site’s owners – the National Trust of England, Wales, and Northern Ireland (National Trust). Ever since the site became a tourist attraction in the 19th century, the number of visitors arriving to experience the site’s natural beauty has increased steadily. In 2017 and 2018, the number of visitors surpassed one million for the first time, and the visitor center built in 2012 was showing the impact of overcrowding. The local community expressed frustration over the impact of the recent significant increase in tourism on their quality of life, on the local economy, and on the conservation of the site.

In 2018, the National Trust established the position of Responsible Tourism Manager at the Giant’s Causeway, and in 2019, as part of a new study, prioritized engaging the local community in the decision-making on a far deeper level. Engagement consultant Cillian Murphy was hired by the National Trust to oversee this work, and given the generations-old conflicts in the region, he included a veteran of community engagement and conflict resolution in Ireland on his team. They recommended a 15-month process of engagement, with the understanding that ongoing engagement would be key to building trust and achieving a successful outcome.

“Many suggested a 6-month plans for community engagement, just to tick off a box. The one we established for the National Trust at the Giant’s Causeway is for 15 months, with multiple conversations and lots of tea. It is at the fifth social setting where you get the real story, not the first,” says Murphy (quoted in a 2021 case study of the Giant’s Causeway).

Often one of the obstacles to regenerative tourism is the difficulty of bringing the local community voices forward when there are powerful stakeholders with contradictory interests. “Unfortunately, it is not until facing a crisis that many stewardship organizations begin to see the benefit of putting local residents at the center of decision making for their communities,” notes the International National Trusts Organisations (INTO) 2021 report entitled Putting the Local into Global Heritage. A key lesson learned from the process at the Giant’s Causeway is that deep, authentic, and lasting engagement with the local community is crucial in building long-term trust.

Moonta Mines, Australia

© National Trust of South Australia

The National Trust of South Australia is on a journey to regenerate tourism as well. As the organization’s CEO Darren Peacock said at the 2022 National Trust Conference, “It’s a moment for thinking differently that should not be missed.”

The Trust of South Australia owns a nationally designated heritage site, Moonta Mines, which they are now redeveloping. The Narungga people are the Traditional Owners of the Moonta Mine site which sits on 300-hectares of land. In its heyday, Moonta was one of the richest copper mines in the world, but mining ceased abruptly 100 years ago, in 1923. The site is a post-industrial landscape, filled with many industrial relics such as old boilers left where they landed, and copper residue everywhere as the copper was sorted manually outside, once lifted from the mine.

In redeveloping this site, the Trust is asking many questions such as “Whose place is this?”, “Whose stories should we tell?”, “How do we share them?” and “What are the story sharing activities that we should undertake?”

The traditional story told is of the successful copper mining business bringing an influx of miners from Cornwall, England to the region. But there are many other stories to tell, such as the children working in the mine, known as picky-boys, and the story of who was on the land before the mine was built. These aspects are now being developed as well.

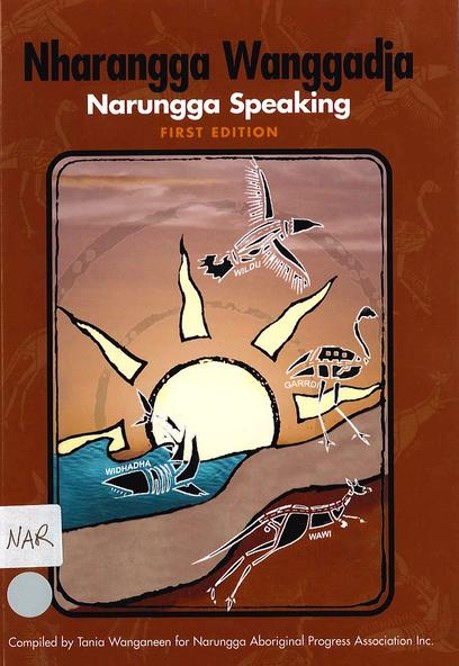

The Narungga people in Australia have been working together with the National Trust of South Australia to regenerate the stories being told at the site. The Narungga people in Australia have also been regenerating their own language and are now renaming and sharing stories with a Narungga voice at Moonta Mines.

In the meantime, the National Trust of South Australia is putting in walking and cycling trails around the 300 hectare site, allowing people to really explore the place in depth. By giving guests access to the complex stories being told both inside and outside the heritage site, creating areas for play and doing historic research as well, the Trust is giving guests a chance to make their own heritage.

“By putting the people both past and present back into an abandoned industrial landscape, we allow heritage to do its best work,” says Peacock. “Our goals for the community and connections we make are resilience, creativity and in particular the sustainability of the practices that happen there.”

First Story Toronto, Toronto

First Story Toronto is an Indigenous led, community-based organization that researches and shares Toronto’s Indigenous presence through storytelling walks and other initiatives. It was started in 1995 by activist and Knowledge Keeper Rodney Bobiwash after noting that Torontonians tend to think of their city as a ‘new’ city: Locals thought of Toronto’s story as wholly determined by the settler, colonial stories of the last 200 years and had little understanding of or connection to the larger Indigenous history of the territory.

Bobiwash created a three-hour bus tour called the Great Indian Bus Tour of Toronto and this one tour has led to an ever expanding and deepening understanding of the Indigenous geography of the city. Over the years, many more people have become involved in this program, including youth, Elders, artists, and other citizens contributing to the knowledge of the Indigenous geography from various perspectives. Through this work, places from Mississauga to Scarborough have been increasingly storied.

The tours are led by a knowledgeable and growing group of Indigenous guides. The guides are paired up to help them understand each other’s perspectives but also to enrich the narrative of the tours. First Story pays guides well, and it’s an important employment initiative – especially for youth, who gain experience, add their voices, and have their own voices heard by a diverse audience.

Their approach is evolving. Dr. Jon Johnson, Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto and lead organizer for First Story Toronto said at the 2022 National Trust Conference that “there is a kind of uncomfortable placement of this initiative as a tour and thinking of it potentially as something for tourists. I think that can invite a certain type of spectatorship and participation which are not in keeping with what we understand this event to be”.

He went on to explain that they have sometimes experienced unethical participation, voyeurism and a level of extraction on the tours. (Extraction refers to using Indigenous Knowledge Experts, not as experts, but as subjects to be studied, and from whom information is extracted and used, often without permission.) First Story is responding with new strategies. For example, they now ask participants to do some homework in advance of the tours. They are more selective on who they bring on the walk with them. And they sometimes refuse to answer questions that are insensitive.

First Story Toronto is an example of regenerative tourism in practice. Asking tour participants to reflect on ethical participation, giving voice to a complex array of Indigenous understanding and storytelling, and setting boundaries for the guests leads to a more positive experience for the community and a positive evolution of the tourism economy.

These are but three examples of the changes that Heritage Tourism is undergoing. They all include a greater sensitivity to the local community and working together with all groups involved to ensure a beneficial and ethical outcome for all – bringing communities and historic sites into the heart of the conversations about tourism.