Making Obsolescence History: Confronting Barriers to Accelerate Building Reuse in Canada

When Natalie Voland, President of Quo Vadis- Gestion Immobilière in Montréal (a Certified B Corporation) approached mainstream banks about financing her early heritage building reuse projects, she quickly ran into a brick wall. “If you’re looking for a loan, banks need to be able to plug in four to ten comparable properties to make their lending formulas work,” explains Voland. “Heritage buildings are often so unique that it becomes really difficult, and the banks won’t offer you money.” Even if they do consider financing, banks will typically only offer a loan-to- value ratio of 50% of the value of the property. In other words, a $3 million dollar property with $4 million in rehab costs will only be offered a loan of $1.5 million – the other $5.5 million in purchase and rehabilitation costs will need to be found elsewhere. Welcome to the challenging world of heritage property development .… even as a social enterprise.

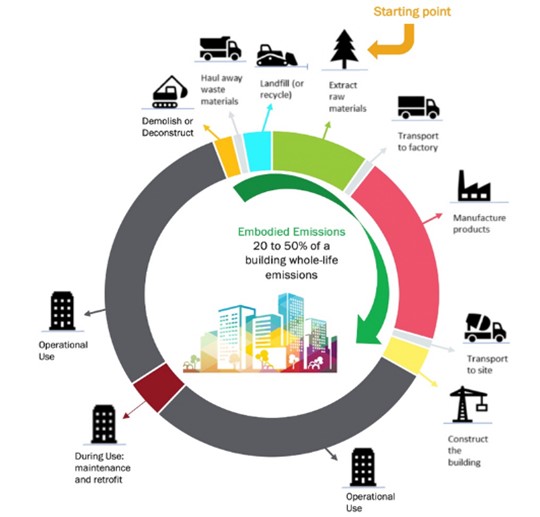

This graphic from C40 Cities Clean Construction Forum (2019) research vividly shows how embodied emissions account for up to 50% of building’s lifetime emissions.

“Reduce, reuse, recycle” is a mantra that has been with us for decades, and when it comes to buildings and climate change impact, a mounting body of evidence emphatically shows us that “the greenest building is the one that already exists.” While many older buildings need operating energy performance upgrades, the building materials in these structures represent embodied energy and avoided environmental impact that are indispensable in Canada’s carbon reduction quest. And yet, rehabilitation is still difficult, creating barriers like the financial ones Natalie Voland experienced. It is far easier to demolish and build new. But why is that? What is standing in the way? Many international studies have explored the best incentive mechanisms to encourage heritage rehabilitation, but very few have probed the underlying barriers to adaptive reuse activity at any length. This is especially true in the Canadian context. For instance, while the 2014 National Trust study Financial Measures to Encourage Heritage Development summarized the “disincentives” to reuse, we knew we needed to go further. What are the key barriers holding the industry back? What systematic changes and culture shifts are needed to make heritage reuse the norm at an industry level? At a national level?

Released this past November, the National Trust’s report Making Reuse the New Normal: Accelerating the Reuse and Retrofit of Canada’s Built Environment report grew out of the recognition that in order to solve these entrenched problems, we would first need to map the current property development system and spotlight key barriers. What we found is that the issues fell into four broad categories:

- Cultural Barriers – Attitudes and Practice Privilege “The New”

Ivan Beljan, of Beljan Developments is single handedly turning the Edmonton property development scene on its head by taking small, unassuming heritage buildings and transforming them, adding sensitive infill, and achieving catalytic impacts on entire city blocks. “Local developers have done the same work for generations and they have an easy formula and financial model that works. They don’t really see a need for a new model,” Beljan reflects. While born and raised in Edmonton, he spent years in Europe which shifted his perspective. “It hasn’t made sense [yet] for local developers to focus on old buildings. Their model has always been buying property to demolish and change.”

Beljan Development’s rehab of the Tipton Investment Building (1914) in Edmonton’s vibrant Old Strathcona area, involved shifting the historic building sideways to create a funky alley giving access to a commercial addition at the rear. Photo: Jim Dobie.

Research for Making Reuse the New Normal confirmed Beljan’s experience is not unique. The Canadian development and construction industry is largely focused on erecting new structures, new construction, and industry players do not develop the skills to adequately evaluate and troubleshoot existing buildings for reuse. This lack of expertise shapes investment decisions by banks, influences the mentorship of the next generation of workers, and creates a self-perpetuating cycle of demolition and new construction.

The consumer marketplace and the engrained modern culture of obsolescence also play a decisive role. Buildings are discarded because it is easy to do so, and consumers continue to privilege new things and the ‘progress’ they signal, over reuse. Well-constructed single family character houses are demolished for larger new ones, often with materials of a diminished quality and life span. Despite wishful thinking there are typically no intensification gains to help justify trashing the older house – the floor space is often much larger, but the same number of people live in the new “dream” home as the old one. Ultimately, all Canadians bear the immediate and long-term environmental costs of these individual property decisions, and will face the challenge of adapting these unsustainable homes in the future.

- Physical or Technical Barriers

While the development industry is skewed in favour of new construction, contemporary construction practices and products are also improperly used on old buildings. These are often not a good fit. Heritage developers across the country underscore how crucial it is to understand how old buildings are constructed and work on their terms. But that knowledge base is limited and often concentrated in metropolitan areas – Vancouver, Montreal, Toronto, Ottawa. What happens when owners need advice in rural Newfoundland, for instance?

Developer John Norman of Bonavista Living in Newfoundland says the tradespeople he works with in the Bonavista area and have been working hard keeping Newfoundland heritage skills alive locally. “It is very difficult to find these skills in other communities or cities in the province, even in St. John’s,” Norman explains. “Most of our tradespeople are Bonavista born, raised, and were trained at our local college that offered heritage carpentry about 15 years ago. We now look for certified carpenters of a high skill set and train the heritage pieces ourselves, in the absence of any available formal heritage training.” This is a hidden barrier across the country, as building owners get misleading advice and repair quotes from tradespeople who don’t have the necessary skills. They will often push owners to inappropriate repairs or demolition.

The George Templeman House (61 Church St.) in Bonavista, NL built in 1872, was vacant for many years, and carefully rehabilitated by Bonavista Living in 2016. It is now home to the Boreal Diner & Broken Books.

Accumulated deferred maintenance is another form of threat to heritage reuse, and one that may lead to the demise of the beautiful Église Sainte-Marie in Church Point, Nova Scotia. Erected 1903-1905 by 1,500 local volunteers, it is the largest wooden church in North America (taller than the Statue of Liberty!) with each of the 70 foot columns in its nave hewn from local trees. With a current repair deficit of $3,000,000, including interior damage from a leaking roof, the local Catholic Diocese has given local volunteers until 2021 to raise the necessary funds, or demolition will follow.

Another challenge is the limitless availability of demolition permits from Canadian municipalities. And they’re cheap: a demolition permit for a 1,500 sq ft home in Calgary costs a mere $337.79. In Montreal, that cost would be as high as $1,200, but is that price point even high enough to seriously influence decision-making towards rehabilitation? The cost of demolition and the subsequent dumping fees at the landfill sites are also unsustainably low, with space for landfills becoming limited. A broader problem that needs urgent attention from the industry is that new construction material ratings do not reflect the true environmental cost of their production, from the carbon outputs required to source and fabricate them to the environmental repercussions from single use components destined for the next generation’s landfills.

Minchau Blacksmith Shop, Edmonton, AB. Listed on the National Trust 2018 Endangered List in 2018, it was demolished in September 2020 – a victim of spot upzoning and limited funding.

- Regulatory Barriers

There are a broad range of regulatory challenges including the shielding of building reuse from other competing government priorities – e.g. public health, transportation, parking – and adaptation barriers within building codes which follow new construction formulas and deter regulators from finding creative solutions.

Demolished this past September, the Minchau Blacksmith Shop in Edmonton, Alberta is a poster child for the key challenges of excessive development potential and flawed provincial heritage legislation. Built in 1925, this one-storey brick industrial building was one of a rapidly dwindling number of boomtown structures in Old Strathcona, a historic district experiencing unprecedented development pressure. City officials negotiated unsuccessfully with the owner for three years to try to incorporate the building into a new development on the site, but had little leverage as the site had been outrageously spot zoned in 1987 for up to 12 storeys. Edmonton was also hampered by the Alberta Historic Resources Act, which, unlike legislation in most other provinces, requires municipalities to compensate building owners for lost development value when it proceeds with heritage designation without the owner’s consent. This controversial Act, while designed to protect the rights of property owners, has only created further barriers in cultivating positive attitudes towards heritage designation and innovative reuse.

- Economic and Marketplace Barriers

The challenges of financing heritage and existing building reuse projects broadly noted in the report, as is the absence of substantial, transformative income tax-based incentives like those that have transformed the marketplace in the United States.

Rising property taxes has emerged as a key challenge, particularly in cities like Toronto where rapidly rising land values (based on “highest and best use” for high-rise redevelopment) lead to escalating property tax assessments. A recent high-profile example of the inherent challenges is 401 Richmond in Toronto, a renowned social enterprise incubator. Despite their widely recognized social value they were almost driven off their property by out of control property taxes. Taxes for the building rose from $446,689 in 2012 to $846,211 in 2017, and were set to hit a whopping $1,286,800 by 2020. 401 Richmond became a high-profile symbol for the distortions of the system in Toronto, which have gone largely unchecked. In 2018, a boutique property tax solution designed for community arts spaces like 401 Richmond was instituted by the City of Toronto, but the larger issue remains and pushes older buildings to premature demolition.

So what’s next with the ongoing Making Reuse the New Normal project by the National Trust?

A developers and stakeholders summit to further test and refine our assumptions at the table with the people who draw up the plans, spend the money and knock down the buildings.

In Ottawa, the Canadian federal government is looking towards zero-net carbon goals by 2050 and the innovative reuse of buildings will need to be part of any strategy moving forward. We want to see building retrofit measures identified in the 2021 Federal Budget help spur heritage building reuse, and see building reuse supports in future party platforms in the next federal election.

We need to make reuse the new normal.