Walking Winnipeg’s Past – 6,000 Years in Eight Sites

The grain trade, labour strikes, and extraordinary architecture: three things for which Winnipeg is known today. However, the city’s history runs deeper, manifested in many historic sites that still stand today. Explore Winnipeg’s heritage through these eight sites deeply interwoven with the city’s at-times-tumultuous past.

1) The Forks & Indigenous History

Photo Credits: The Forks Winnipeg

Archeological discoveries at The Forks provide testament to the long past of the land now occupied by the city of Winnipeg. The site, whose name refers to the “forked” confluence of the Assiniboine and Red Rivers, has been a site of human use for at least 6,000 years. The Forks was inhabited seasonally by Indigenous peoples who came to fish and hunt, taking advantage of the rich source of sturgeon, sauger and walleye in the rivers, and deer, elk and bear in the forests and plains. By 1000 BC, groups were camping here for long periods, taking advantage of the site’s location as a major transportation and trans-continental trade route. Early residents left behind a hearth, complete with catfish bones and stone flake tools, and products originating from as far away as Texas and Lake Superior.

In 1738, the first Europeans arrived via canoe. Hoping to trade furs, they established several forts near the The Forks because of its millenia-long significance as an Indigenous trading place. The Europeans built a substantial relationship with the Assiniboin in particular, who at that point occupied the site. They became middle men in the fur trade, exchanging their used European goods for furs with other Native groups, then bringing those furs to the Europeans for a profit. The site remained an important hub for fur trading until the late 1800s, when grain production took over as the region’s primary industry. The site, also home to mass railway development, was later nicknamed the “Gateway to the Canadian West” as a result of its importance to immigration in and through the area.

History marker: Walk out to the Red River, and look across to historic St. Boniface, cradle of the Franco-Manitoban community. Many of the buildings at The Forks are historic; Peek into the Forks Market, occupying the former horse stables of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and the Great Northern Railway, and the Johnston Terminal, once a railway warehouse.

2) Exchange District National Historic Site & Industry

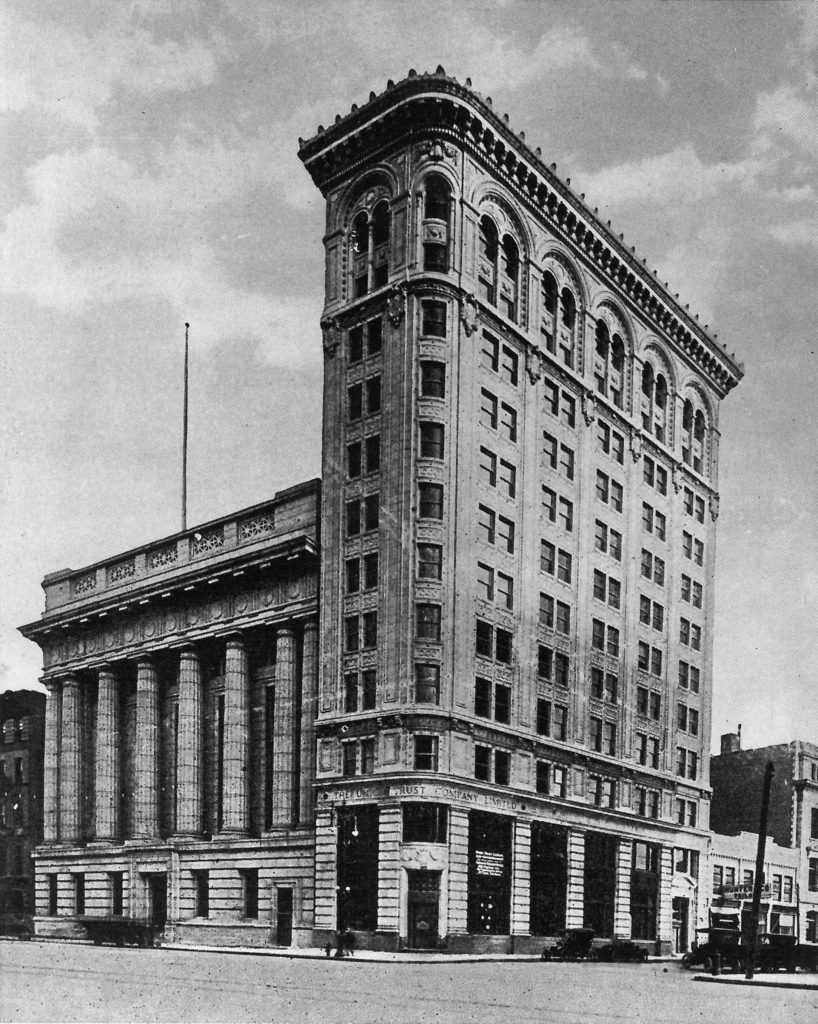

Photo credits: Winnipeg Architecture Foundation

As the grain industry blossomed in the late 1800s, so did Winnipeg’s downtown core. The Exchange District, named as such after the Winnipeg Grain Exchange, formed the centre of the Canadian grain industry at its height. Between 1881 and 1911, the city’s population skyrocketed from 25,000 to 135,000, making it the country’s third largest city after Montreal and Toronto. As commercial activity slowed during the two World Wars, during which development shifted south of the Exchange District, the area was left largely untouched, making it one of the most historically-intact early-20th-century commercial districts in North America. Known as a “living, breathing set” in the film industry, the area was key to attracting $685 million in Canadian/US production to Manitoba between 2003 and 2008.

History Marker: Most of the massive warehouse buildings in the Exchange are constructed of wooden beams and heavy, load-bearing masonry walls. Because it was so fast growing, Winnipeg was often nicknamed the “Chicago of the north” after the rivalling American up-and-comer. As such, much of the architecture along Main Street was influenced by the “Chicago Style” of steel-structured, curtain-walled skyscrapers. Be sure to note the Union Bank, Canada’s first “modern skyscraper” in this regard. The Union Bank is now occupied by the Red River College’s Paterson Global Foods Institute.

3) St. Boniface & Franco-Canadians

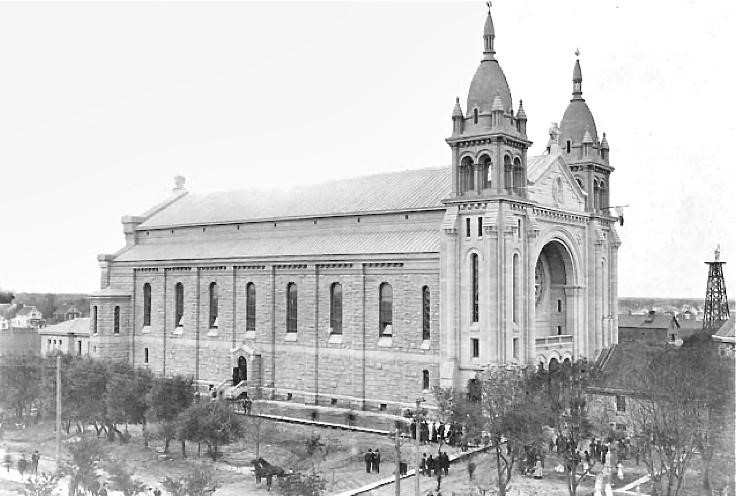

The Saint Boniface cathedral remains the principal church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Saint Boniface, and serves in particular the Franco-Manitoban community. The area now known as the city ward of Saint Boniface has been home to Franco-Manitobans and Métis for two centuries.

The European fur trade led to marriages between the French and Indigenous peoples, which produced descendants called Métis. This group, instrumental in the fur trade as skilled hunters and traders, eventually gained a distinct sense of identity as a unit, both politically and economically. In 1869, when the Government of Canada acquired the land they occupied, the Métis joined forces to stand up for their rights. Louis Riel, a Canadian politician and the celebrated founder of the province of Manitoba, spearheaded two resistance movements against the government of Canada and then-prime-minister John A. Macdonald, becoming a hero to French Canadians and Metis peoples in the face of an encroaching Anglophone national government. Walk through the St. Boniface cemetery near the cathedral – Louis Riel is among several notable figured buried there.

Photo credit: Winnipeg Architecture Foundation

History Marker: As a result of rapid urban growth, public buildings in Winnipeg often struggled to keep pace. Early on, in 1818, the first church in western Canada was established near this site in Winnipeg. In the next century, the church would be rebuilt four more times, each larger than the one before it. The last church, completed in 1905, was able to accommodate a congregation of over 2,000. However, this cathedral was mostly destroyed by fire in 1968, leaving only the remains of the grand Romanesque-Byzantine façade in the back of which the modern day church has been constructed.

4) Winnipeg General Strike Statue & Labour Politics

Photo credits: L.B. Foote collection – Archives of Manitoba

Even alongside the blossoming of grand buildings in Winnipeg, conditions for workers left much to be desired. The First World War had worsened the already-impoverished state of the working class, who now dealt with the physical and psychological effects of war in addition to unstable employment, health and housing conditions. Wages simply could not keep up with the cost of living, which had already risen by 64 per cent in 1913. Furthermore, soldiers returning from overseas found that their employers had profited greatly from the war, further widening the inequality gap and heightening resentment.

After a year of semi-successful attempts to form unions, and inspired by the Russian Revolution two years prior, 30,000 workers walked off their jobs at 11:00am on May 15, 1919. Virtually the entirety of Winnipeg’s working population went – and stayed – on strike for what would turn into a six-week affair, triggering sympathy strikes across the country. Although it eventually ended in defeat, and in a few cases, bloodshed, the strike laid the groundwork for better labour conditions and union representation for the Canadian working class.

History Marker: Tension culminated on June 21, 1919, when thousands of strikers took to the streets in a silent parade on what later came to be known as “Bloody Saturday.” What began as a peaceful demonstration quickly devolved into police gunfire, and a streetcar was tipped off its tracks and briefly set on fire. Several people were killed and over 80 arrested. The streetcar statue commemorates the tipping of the streetcar as a turning point in the Winnipeg general strike.

5) Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre & Modernism

Photo credits: Manitoba Theatre Centre

Winnipeg was a site of major urban renewal during the latter half of the 20th century. In the 1960s, the city was both celebrating post-war prosperity and grappling with a downtown in decline. Industry and manufacturing, as in many North American cities, made the move out of the city centre and into the suburbs, leaving the city’s once-crucial warehouses to fall into disrepair. Paralleling the urban renewal schemes involving large-scale demolitions in downtowns across Canada, Winnipeg embarked on the demolition of a large section of the northern Exchange District for a new Civic Centre with striking mid-century modern architecture: City Hall, Public Safety Building, Concert Hall, Manitoba Museum, and Manitoba Theatre Centre.

One of these mid-century styles embraced by Winnipeg was Brutalism, a style that embraced the heavy, rough or unfinished aesthetics of masonry, and particularly celebrated bare concrete impressed by wooden forms. The Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre (RMTC), completed in 1970, exemplifies brutalist design in the city, intended to attract people to the city centre and project a civic image of “progress” and modernity.

History Marker: Brutalism is finding renewed popularity around the globe and the RMTC building has been recognized as a nationally-important architectural landmark. Look for the maroon plaque outside the building. The site earned a National Historic Site designation in 2009 and a royal designation from Queen Elizabeth II the following year. In April of 2019, it was awarded the Prix du XXe siècle by the National Trust and RAIC for its brutalist architecture.

6) Millennium Centre & Conservation

Photo credit: Heritage Winnipeg

Urban renewal often breeds controversy – as was the case following its spread in Winnipeg. The Millennium Centre, originally the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, is a testament to the power of public outcry in the face of the bulldozer. In the late 1970s, Winnipeg’s modernist movement was at full swing, and the Millennium Centre, a 1911 Beaux-Arts bank building, was in its path. It was proposed that the building be razed to make room for a parking lot, eliciting outrage from local heritage supporters. The resulting banding-together of citizens upset with the proposed knockdown catalyzed the heritage movement in Winnipeg, and found a true leader in David McDowell (1938-2019), a tireless heritage educator and activist who sadly passed away this June. The battle around the Millennium Centre led to the creation of Heritage Winnipeg, which was formed by the City of Winnipeg, the Province of Manitoba, and the National Trust for Canada (then known as the Heritage Canada Foundation). Heritage Winnipeg, a non-profit promoting the conservation of Winnipeg’s built heritage, owns and operates the building today.

Photo credits: Winnipeg Architecture Foundation

History Marker: Note the building’s façade. The structure is architecturally significant for its marble banking hall and glass dome, and is representative of the opulent architecture typical of banks of the era. It’s also the physical manifestation of the spirit and determination of Winnipeg’s citizens in the face of urban renewal deemed too extreme.

7) Red River College Exchange District Campus & Adaptive Use

Photo credits: Red River College

While proponents of urban renewal and architectural conservation have clashed at several points during Winnipeg’s history, in recent years the past and present have been combined in adaptive reuse projects that preserve the city’s character while providing modern functionality. The Red River College’s Exchange District Campus is a striking example of this, though controversial at the time for its adaptation of the existing historic structures. The Roblin Centre, completed in 2003, blends historic and modern design, maintaining original 1880’s building facades and other original elements left over from Winnipeg’s economic boom time. The campus’s Heavy Equipment Transportation Centre was recognized for its Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Certification, becoming one of the first education centres in Manitoba to receive the title.

History Marker: Look for the original elevator shafts and safes, now scattered around the buildings. Make special note of the Heritage Room, used in the early 1900s as a boardroom for the Grain Exchange. During the creation of this room, each piece of wood was numbered so it could be replaced in the exact same formation. The bookstore also makes use of original glass, columns and two original radiators, which are mounted inside.

8) Canadian Museum of Human Rights & New Directions

Photo credits: Aaron Cohen/CMHR-MCDP

In 2003, 21 years after the signing of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Canadian Museum of Human Rights made headlines for the very first time. It was announced as a joint project between all three levels of government, The Forks North Portage Partnership and the Asper Foundation. The Museum of Human Rights would go on to be the first new national museum since 1967, and the first national museum outside the National Capital Region. The museum was designed by Antoine Predock, an architect from Mexico, whose design was selected through international competition.

The spiraling architecture of the building is based on an upwards journey, representing the struggle towards human rights for all. The nature-inspired design is grounded in four “Roots,” symbolizing humanity’s connection to the earth. The irregular form and building materials, including basalt stone, alabaster and limestone, created unparalleled challenges during construction – however, the resulting building successfully elicits a strong emotional response about the journey to enlightenment.

History Marker: Walk the museum grounds. The site of the new building is one of rich archeological value, and excavations prior to construction garnered more than 400,000 artifacts which archeologists said dated back to 1100 AD. Attend the National Trust Conference 2019 (October 17-19, 2019) and enjoy unparalleled access to the museum’s galleries during the conference’s Closing Celebration.

The National Trust’s conference, Heritage Delivers: Impact, Authenticity, and Catalytic Change is being held in Winnipeg this year. Join us and explore the catalytic power of historic places. While in Winnipeg, discover the history, culture and spirit of the city through one of the unique walking or bus tours being offered during the conference – Oct 17-19, 2019.