Tse’k’wa Heritage Society

Tse’k’wa (or “Rock House” in Dane-zaa/Beaver language) is a cave site near Charlie Lake in Northeastern B.C. that tells the story of 12,500 years of continuous use by the Dane-zaa ancestors. The site is owned and managed by the Tse’k’wa Heritage Society, a collaboration of three Dane-zaa First Nations: Doig River, Prophet River, and West Moberly First Nations. “The work at Tse’k’wa is really about making a sacred place come alive,” says Board President, Garry Oker. “And one of the key ways of doing that is by integrating the teachings of Indigenous Elders and the Dane-zaa language into the experience of the site.”

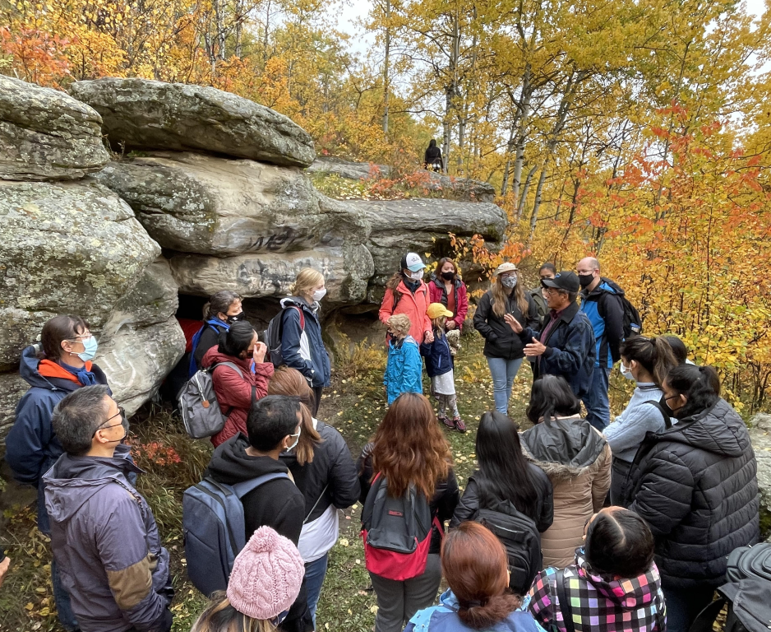

Visitors gather at the Tse’k’wa Cave site. Photo Credit: Tse’k’wa Heritage Society

Recently reclaimed by the Dane-zaa, Tse’k’wa is an exceptional heritage place. It is a rare example of a site that preserves a complete archaeological record from the end of the last ice age to recent times. This record provides tangible evidence and proof of the Dane-zaa connection to the land and longstanding presence in the area. Recognizing the need to protect the site, the Society purchased the property in 2012 and have been tirelessly advocating for its recognition; in 2019, it was officially designated as a National Historic Site of Canada. In 2024, it was granted official artifact repository status by the BC Archaeology Branch, which will allow for the repatriation and display of the thousands of artifacts and animal bones excavated by Simon Fraser University (SFU) archaeologists at the site.

Tse’k’wa Heritage Society Board of Directors and Elders (L-R) Dianne Bigfoot, Gary Oker, and Laura Webb. Photo Credit: Tse’k’wa Heritage Society

Connecting the archaeological artifacts to the living heritage and lifeways of the Dane-zaa peoples will be critically important. “For the Dane-zaa people, Tse’k’wa is more than just a physical location. It is a sacred space that embodies our sense of place and identity” says Garry Oker. One of his favorite discoveries at the site is a 10,500- year-old stone bead that shows a cultural tradition the Dane-zaa people still practice today. Similarly, the site contains ancient bison bones hunted by Dane-zaa ancestors dating back to the time of the wǫlii nachíí (giant animals).

Examining artifacts gathered at the Tse’k’wa site. Photo Credit: Tse’k’wa Heritage Society

“People often talk about UNDRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples),” says Oker, “but it often isn’t connected to action. It is just words. That is why learning traditional teaching and practices from Elders at the site is so important. In the Dane-zaa creation story, we are taught that if you want something, you make it yourself. That’s what we want to see happen at Tse’k’wa.” Managing the archaeological site is only one part of the Society’s broader mission to gather, preserve, and celebrate Dane-ẕaa language, culture, and heritage. Their goal is to steward a place where old stories and new teachings can meet.

Examining beadwork at the Tse’k’wa site. Photo Credit: Tse’k’wa Heritage Society