Heritage on the Hotseat

Earlier this year a polling firm surveyed 1,000 Canadians across the country about their views on heritage places and the field of heritage conservation.

Commissioned by the National Trust, and building on a 2020 poll, the survey targeted a general audience, and included questions like How interested are you in efforts to conserve heritage places? and What are the most important reasons to conserve them?

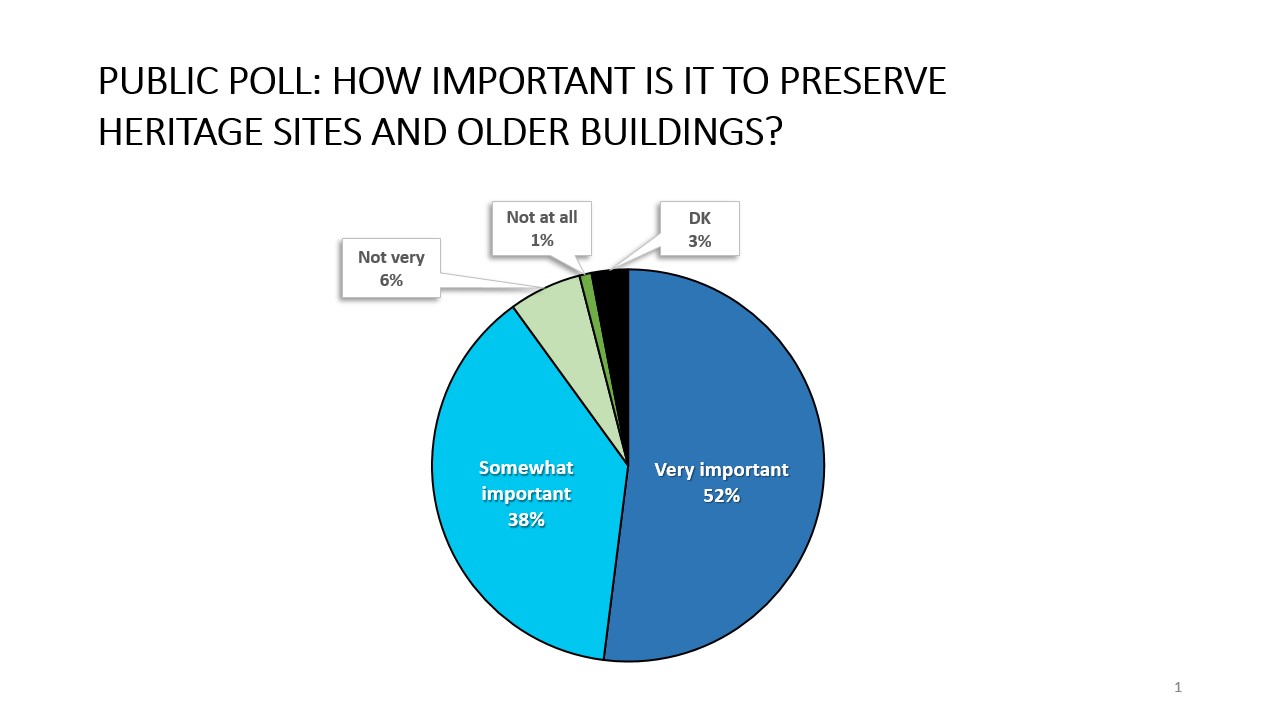

The responses reveal strong agreement on the importance of preserving heritage places and sites – to the tune of 89% – and give clear signals about why Canadians care.

90% of Canadians feel it is very or somewhat important to preserve heritage sites, historic buildings, older neighbourhoods and districts. The sub-group of people who are aware of 10 or more heritage sites skew even higher in believing preservation is very important, to the tune of 71%.

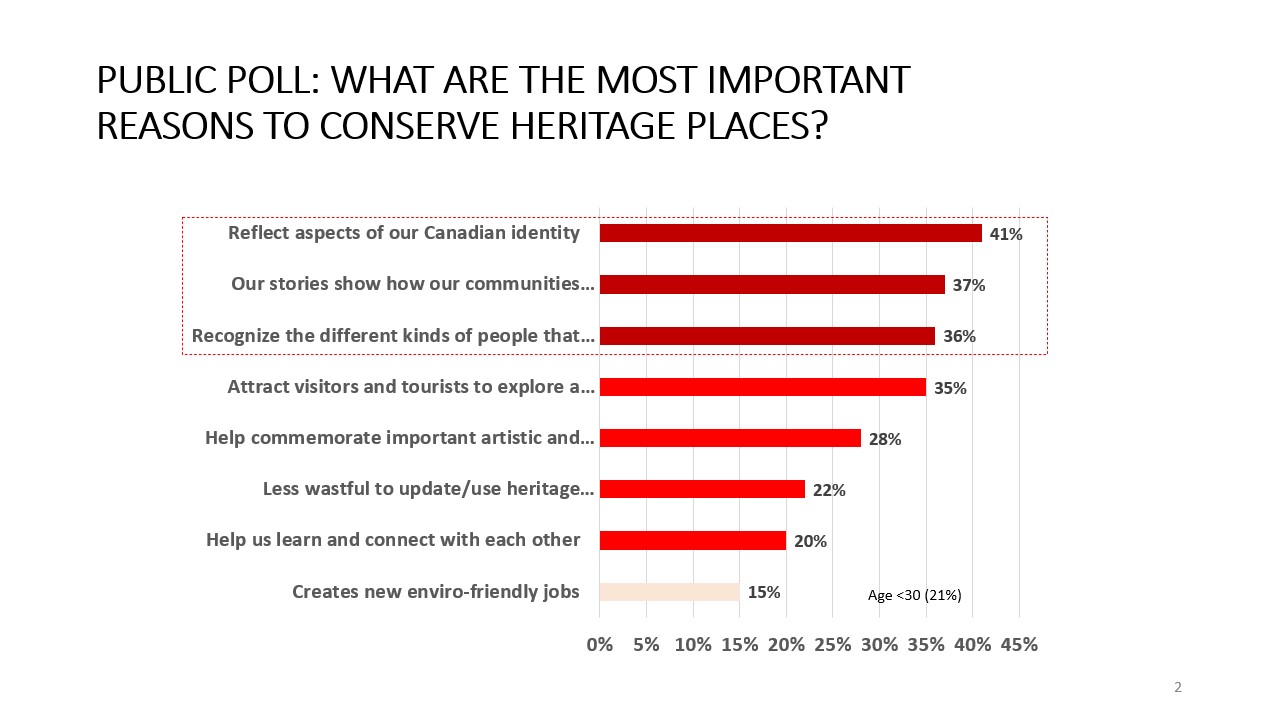

Topping the list of motivations to preserve: that heritage places reflect aspects of our Canadian identity; and that their stories show how our communities have evolved, and reflect the different people that make up our history.

For the general public, reasons to conserve relate to our country, stories, people and communities. Those age 70 and older believe even more strongly in the connection to Canadian identity (62% compared to 41%).

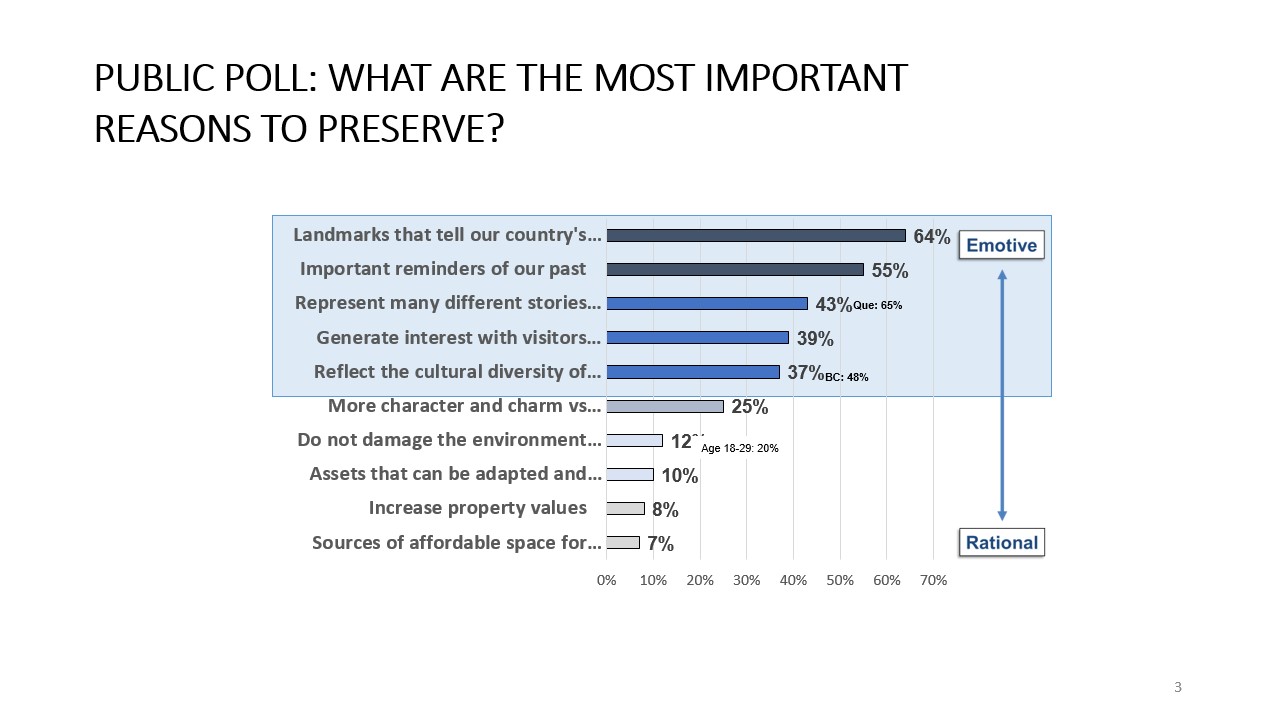

These findings mirror a 2020 poll that showed people connect with heritage places for emotional reasons, including their role in telling the story of our county and our people. In contrast, the more rational reasons to conserve heritage register as less important to a general audience, with only 12% seeing environmental benefits as a motivation for heritage conservation and only 10% motivated by the potential for adapting and reusing heritage places.

People feel it is important to preserve heritage places because of their role in telling stories of Canada, its people, and its history. The most engaging reasons are emotional rather than practical (e.g. stories versus environmental benefits or property values).

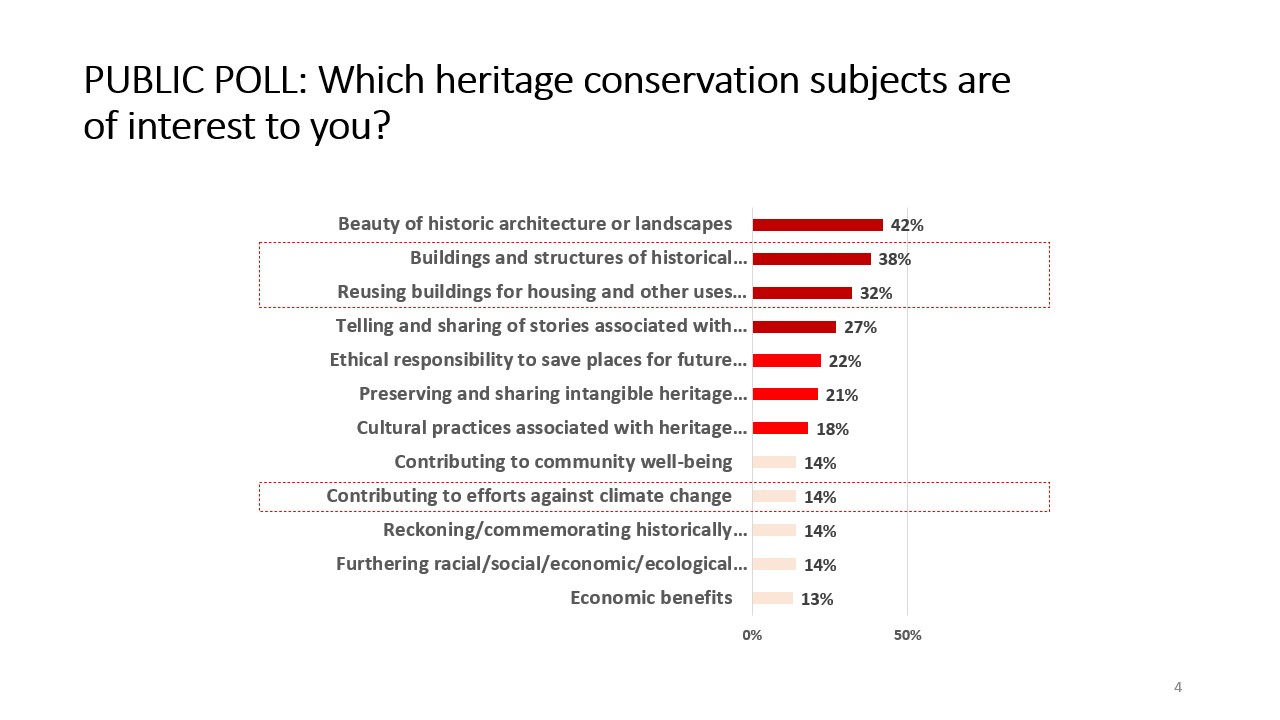

When asked which heritage conservation subjects are of interest, the general population ranked these as their top three: the beauty of historic architecture and landscapes; significant buildings and structures; and reusing older buildings instead of demolishing them.

Members of the general public rank beauty and historical significance as their top subjects of interest.

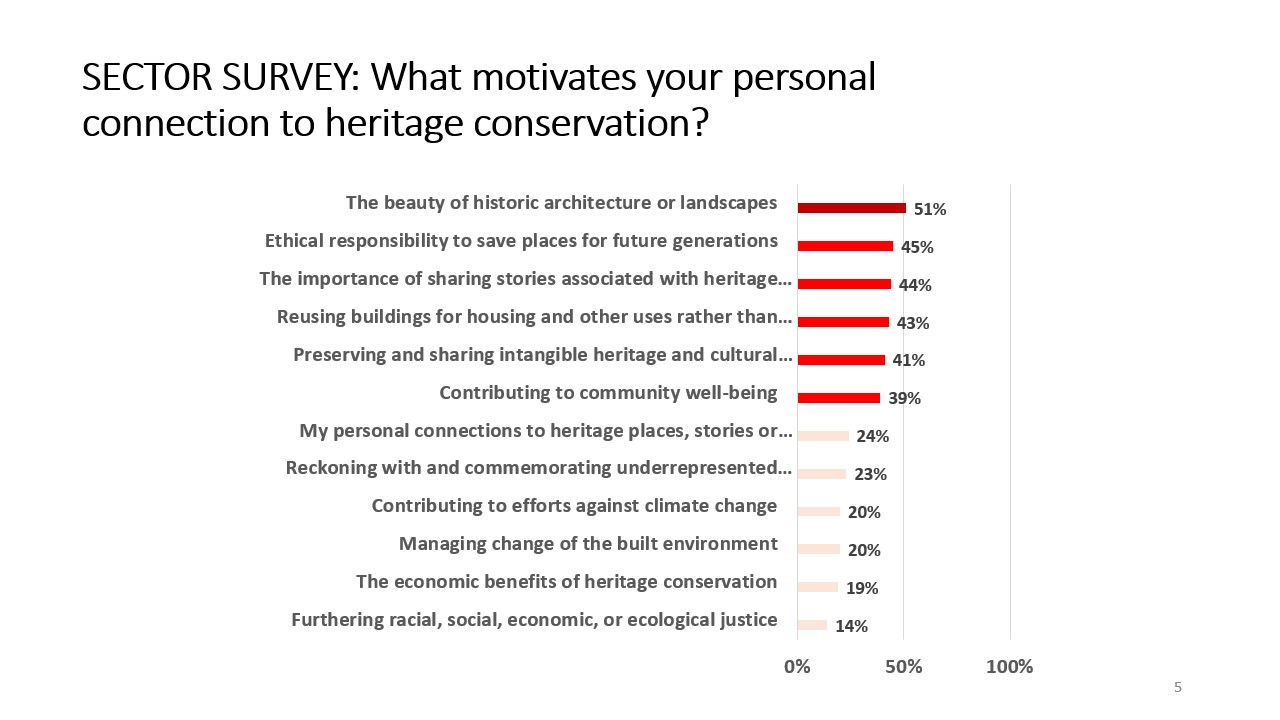

At the same time that the general public was being surveyed, over 500 people involved in heritage conservation responded to a parallel survey designed to get a sense of how the movement perceives its own motivations, challenges and degree of success. Notably, heritage conservationists identified motivations for their work that largely matched the public’s top areas of interest – but also identified key drivers for heritage conservation that were not on the radar for a more general audience: contributing to community wellbeing, and an ethical responsibility to future generations.

While sector respondents report being motivated by many of the same areas of interest that resonate with the general public, the ethical responsibility to save places for future generations and contribution to community well-being stand out as areas that rank higher inside the field.

“It is interesting that the general public may not share the heritage sector’s sense of itself as a field motivated by community wellbeing and ethical stewardship for the future,” says Natalie Bull, the Trust’s Executive Director and project lead for the recent surveys. “The ‘heritage brand’ is certainly getting mixed reviews these days, and the movement is facing some foundation-shaking challenges.” At a moment when reconciliation, diversity and inclusion are front and centre in society, museums, heritage sites and organizations are reckoning with a long history of privileging the dominant narrative. And in some municipalities, heritage conservation is being seen as a barrier getting in the way of developing much needed housing, or a tool for NIMBYs (Not In My Back Yard). In Ontario, that occasional criticism leapt to the forefront with the release of the Ontario Government’s Report of the Ontario Housing Affordability Task Force in February 2022 (and the subsequent More Homes Built Faster Act rushed into law in November 2022). The report called out heritage directly, declaring: “While true heritage sites are important, heritage preservation has also become a tool to block more housing”.

The ‘heritage brand’ is the focus of the Heritage Reset, a project partially funded by the Department of Canadian Heritage and led by the National Trust with a dozen partners and advisors. Through surveys, conversations, outreach and research, the Reset is taking the temperature of the field, exploring how heritage is perceived by key audiences, and gathering examples of how heritage conservation can play a bigger role in social equity, diversity, climate change and housing.

“The sector survey showed that those inside the movement see substantial concerns,” says Bull. “Top issues identified included the movement’s failure to attract adequate public financing, incentives or donations for heritage places; the failure to attract the attention of decision-makers, the media and the general public; and the failure to position heritage as a player in climate action.” Diversity is also an area of concern. Only 50% of respondents perceive heritage conservation to be inclusive, diverse, open and accessible – but only 0.4% of sector respondents self-identified as Indigenous or People of Colour – signaling a substantial lack of diversity among mainstream practitioners.

The data suggests that the heritage movement itself is hungry for change. A full 99% of respondents agree that some degree of change is needed to the field of heritage conservation, with one in five calling for substantial revision.

“Reggae Lane Street Sign.” Little Jamaica, on Eglinton Street West in Toronto, is an area of the city that is being recognized for its cultural heritage. It is a prime example of how the Heritage Conservation field has evolved to preserve a cultural community’s connection to a neighbourhood.

Credit: Mary Crandall, “As I Walk Toronto” Blog

In fact, heritage has a long history of recalibration and reinvention. Evolving from an original focus on monuments, landmarks, restoration and historic sites, the movement found its feet in the era of urban renewal as a social movement concerned with the displacement of communities and loss of traditional neighbourhoods. In the last 50 years, the focus has expanded to include vernacular buildings, downtowns, districts, and cultural landscapes. The heritage conservation field is now as much about everyday buildings and spaces all around us, as it is about special places protected under law or set aside as landmarks. In addition to bricks and mortar, and landscapes, there is increasing recognition of places as gateways to intangible values, ideas and stories. Today, diversity and inclusion and bringing hidden histories to light are being prioritized in the identification of places that merit attention. While there is much to do, it feels like change is well underway.

These threads of change come together in examples like the Little Jamaica Heritage Conservation project – a grassroots effort to preserve a cultural community’s connection to a neighbourhood. This project is not aimed at preserving architecture per se, but at protecting Black businesses and spaces in the midst of a swiftly gentrifying area. “There is a shameful history in North America and around the world that whenever major infrastructure projects or gentrification is approaching, Black communities are usually the first to be displaced,” says Josh Matlow, local councilor for the area. The Little Jamaica project is a great example of how communities can use heritage conservation to serve people and their relationship to place – well beyond a pre-occupation with architecture and the protection of the built form.

Similarly, the Single Room Occupancy (SRO) Renewal Initiative project by BC Housing shows that heritage and affordable housing are comfortable bedfellows, with a social housing project that involved the rehabilitation of 13 heritage buildings from the early 1900s in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Completed in 2017, the project’s primary goal was to provide safe, functional, and habitable accommodations for residents of the Downtown Eastside community, and ensure they weren’t displaced. BC Housing simultaneously achieved these social goals alongside heritage ones by improving all major building systems as well as carefully conserving the heritage features of the 13 buildings during rehabilitation.

As the single largest Public Private Partnership (P3) social housing project in North America, the Single Room Occupancy (SRO) Renewal Initiative project by BC Housing involved the renovation and rehabilitation of 13 buildings in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The above photo displays 3 sites renovated in the SRO initiative

There are many positive examples like these that reflect how heritage conservation can address the current social, economic and environmental challenges facing Canadians. In some ways, the Heritage Reset is about sharing these examples and encouraging the movement to catch up with itself.

Do you have thoughts on the future of heritage conservation and would like to participate in the Heritage Reset? If so, please send a note to Reset@nationaltrustcanada.ca