Fight the Power: Transforming Cities Through a Revolution of Ideology, Imagination, & Values

Stephanie Allen delivered a riveting keynote at the APT – National Trust Conference in 2020 that traced how anti-Black racism in Canada led to the formation and displacement of Hogan’s Alley, the only Black neighbourhood to have existed in Vancouver.

Read her perspectives on what town planning, urban development, and heritage preservation reveal about who and what matters in our cities – and what a revolution of ideology, creativity, and values might offer us as we search for ways to transcend today’s challenges.

I am a real estate developer by profession and recently completed a master’s degree in Urban Studies focused on the settlement and displacement of people of African descent in Canada, British Columbia, and Vancouver. As a descendant of enslaved Africans, I have been almost totally severed from my ancestral heritage, my people, spiritual practices, economic systems, political structures, agricultural practices, building forms, and character. Even my name was stolen from my family through the process of enslavement, replaced by the name of slave owners who imposed Eurocentric systems to subjugate and oppress Black people.

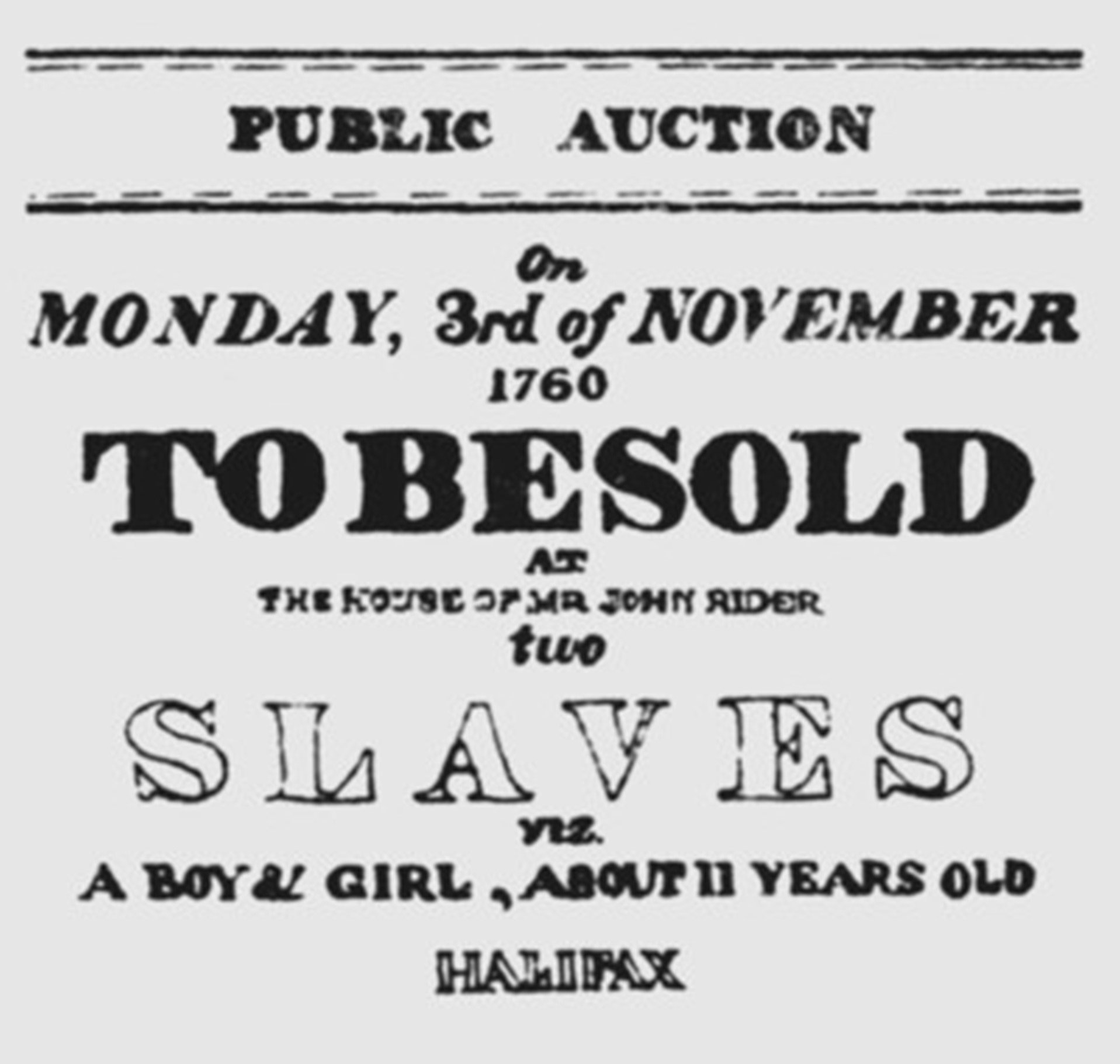

Halifax Gazette, 3 November 1760 Photo credit: Nova Scotia Archives

Canada has a little known and enduring history of anti-Black racism starting with the enslavement of Africans that was practiced over 200 years in this nation. Upon emancipation, the status of people of African descent “changed from a legal condition to a biological condition – from slave to Black.”[1] Unfortunately, emancipation did not mean the end of anti-Black racism for people in the territory that would become Canada, nor did it transform it into a nation where Black people could participate equally in society. As with other nations that held human capital for profit, no reparations were paid to the formerly enslaved to account for the centuries of abuse and stolen wealth, and there were no formal commitments made to racial justice and equity, before and after the abolition of slavery.

Following the emancipation of enslaved people in the British Empire in 1835, Black migration to Canada was selectively sought by governing officials for two reasons: one, as a mean to shore up British sovereignty over lands stolen from Indigenous people; and two, as a deterrent to American territorial expansion. Examples of this include the American Revolutionary War, when enslaved people were promised freedom in exchange for fighting on the side of the British.

Another example of this was when Confederation was being debated in eastern Canada, James Douglas, who was appointed to preside over the first trading posts on the West Coast, found himself dealing with a flood of American miners searching for gold on the Fraser River. Concerned that Americans would overwhelm the sparsely populated colony and create a groundswell of support for US annexation, Douglas went in search of immigrants who might be sympathetic to British interests. Douglas was himself a bi-racial person of African and European heritage, which may have influenced his open attitude towards Black migrants. Douglas reached out to members of San Francisco’s Black community who had been discussing the need to seek refuge from their homelands. In 1857, a US Supreme Court decision had denied citizenship to both free and enslaved people of African descent. Douglas promised them British citizenship after five years of land ownership and full protection of the law.

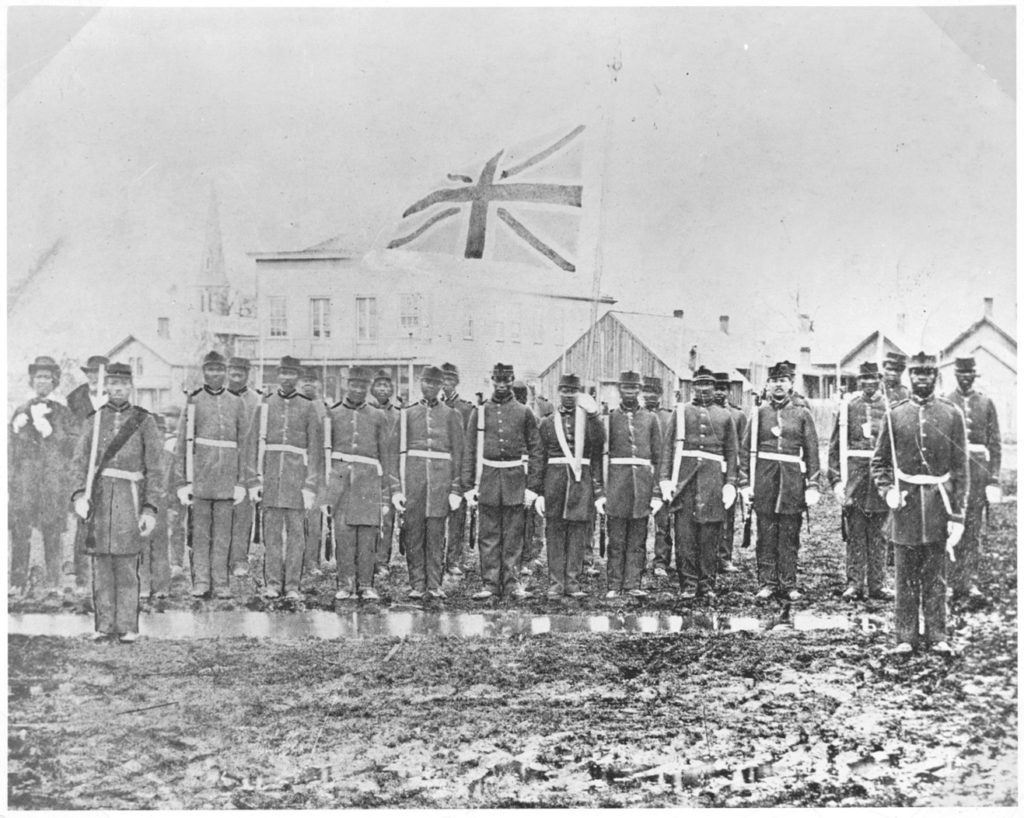

The Victoria Pioneer Rifles (or “African Rifles”). Photo credit: Image C-06124 Courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives, Victoria

In the meantime, the Black community established a 35-member pioneer committee to investigate the offer. The Black delegation who met with Douglas reported their optimism about the prospect of finding refuge in Victoria, saying in a letter: “We’ve determined to seek an asylum in the land of strangers from the oppression, prejudice and relentless persecution that have caught and pursued us for more than two centuries in this our mother country. Therefore, a delegation having been sent to Vancouver Island, a place where which has unfolded to us in our darkest hour the prospect of a bright future to this place of British possession, the delegation having ascertained and reported the condition, character, and its social and political, political privileges and its living resources.”

Not long after that meeting, a wave of Black families from America moved to the territory and relatively quickly some among them gained prominence in their new community, obtaining land claims, and ascending to positions of prestige, including law enforcement, school boards and Civic council. And while their early achievements were remarkable at that time of white domination, the historical record reveals they were still subjected to systemic and interpersonal racism not long after landing in their new homeland. They engaged in every level of the economy striving to become valued citizens in their new home, and yet they remained unvalued. Anti-Black racism was not uniquely American as these asylum seekers soon came to brutally experience.

This very brief historical skim reveals the linkages between Canada’s foundation of systemic white dominance over Black people who were simultaneously subjugated for wealth creation through slavery while being exploited to uphold and protect the sovereignty of the British Empire and fight American encroachment into its colonies. This was the founding of Canada’s version of anti-Blackness: extracting value through exploitation, while perpetuating violent harm.

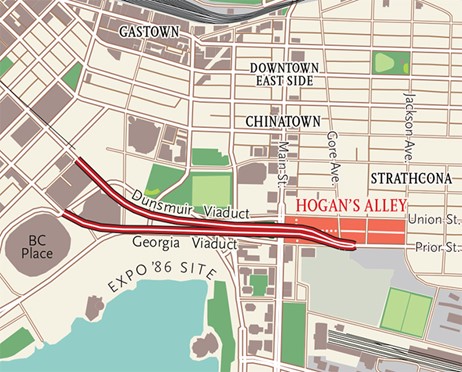

This history also sets the context in which the Vancouver neighbourhood of Hogan’s Alley was established and displaced. Some of the people who settled on Vancouver Island migrated to Vancouver along with Black people from other regions in Canada, the US and the Caribbean. The Black community established itself in the southwest corner of the area known as Strathcona in the late 1800s. It came to be known as “Hogan’s Alley” not because someone named Hogan lived there, but because it was a slang, pejorative given to racialized low-income urban areas in North America based on a comic strip that sensationalized racial tensions found in inner cities. Mrs. Neely, who moved to Vancouver in 1944, recounted in the book Opening Doors, “When I came here, this district was negros apartment blocks that were all full of Blacks.”

Footprint of the Vancouver’s historic Hogan’s Alley in current urban context. Photo credit: Vancouver Heritage Foundation – Places that Matter

In my Master’s thesis, Fight the Power: Redressing Displacement and Building a Just City for Black Lives in Vancouver (2019), I document three reasons why Black people chose to settle in Hogan’s Alley.

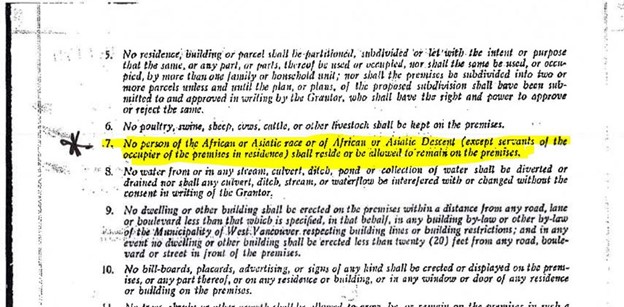

The first reason was due to restrictive land use regulations. Systemic racism was incorporated into planning policies in Vancouver with the help of Harland Bartholomew, who in 1926 was hired to develop Vancouver’s inaugural town plan. Based in St. Louis and America’s first professional town planner, Bartholomew was a devoted segregationist, whose ideologies on race and class reflected the dominant white society’s ideologies and influenced his development of zoning plans for the American cities in which he worked. In 1916, when the US Supreme Court struck down a Louisville, Kentucky city zoning ordinance that explicitly prohibited Black people from moving into majority white neighborhoods, Bartholomew created a workaround. His 1920s St. Louis zoning plan enabled racial segregation to continue by developing distinct land use classifications based on home quality and density. These worked in conjunction with racially restrictive covenants attached to the property contract between the buyer and seller which was acceptable in common law. Bartholomew’s policy design would effectively keep racialized and lower income communities separate from affluent white neighborhoods, circumventing the Supreme Court ruling.

Example of a restrictive covenant on property title in West Vancouver’s British Properties. Photo credit: North Shore News

While Bartholomew’s Vancouver plan was not fully implemented, it was drawn on heavily and his ideas were used to shape the earliest zoning laws in the municipality, the legacy of which remains to this day.

The second way housing discrimination was enshrined was through the adoption of racially restrictive covenants in Vancouver many of which remains on the titles of homes in affluent single-family areas. These covenants, combined with discriminatory rental practices, relegated people of African descent and other racialized groups to the Strathcona area of Vancouver. In 1950, UBC Social Work professor Leonard Marsh observed of Hogan’s Alley residents: “Many of them could afford to live elsewhere, but it’s too obvious that they would be unwelcome.”

Fountain Chapel Picnic 1935, a church located in Hogan’s Alley. Photo credit: Gibson Family, retrieved at Blackstrathcona.com

Therefore, after being zoned out, and restricted from purchasing homes in affluent areas even if they could afford it, the third reason that Black people clustered in this area was its proximity to work and the growth of social networks. Some of the Black men in the community worked as sleeping car porters and Hogan’s Alley was close to the railroad station. It was also where Black entrepreneurs, particularly women, could afford to establish small businesses and restaurants patronized by Black residents, visitors and non-Black people.

In my research, I point to four contributing factors for the displacement of Hogan’s Alley in the 1950s at the height of the federal urban renewal program. First, the 1931 zoning bylaw changed much of Hogan’s Alley and the surrounding areas to an industrial zone, devaluing the homes that were suddenly non-compliant with the land use designation. This made it difficult for homeowners to secure home improvement financing or sell to anyone else, making it impossible for owners to sell their properties to anyone but the City of Vancouver. After buying these properties, the city left them vacant, causing property devaluation in the area. Second, I show how newspaper reports of the day labeled the community as a place of squalor and immorality due to racial bias and ignored the hard-working small business owners, families and church community that was there. This resulted in the people living there being dehumanized and unworthy of support and civic investment. Third, the City also left the neighborhood to fall into disrepair by refusing to invest in public infrastructure such as sidewalks and roads, and at times, not picking up residential garbage for weeks. Creosote was used to spray the city sidewalks and streets to tamp down the dust that was left to accumulate.

View of Hogan’s Alley in 1958. Photo credit: City of Vancouver Archives, Bu P508.35

These three factors combined to have a ghettoization effect on Vancouver’s Hogan’s Alley neighborhood. Despite all the efforts from the community to build and sustain a vibrant enclave that would provide support and shelter them from the dominant racist society that existed at the time, willful neglect, criminalization, and land use changes to devalue homes had a devastating impact on the community. It was primed for the final blow: urban renewal clearance.

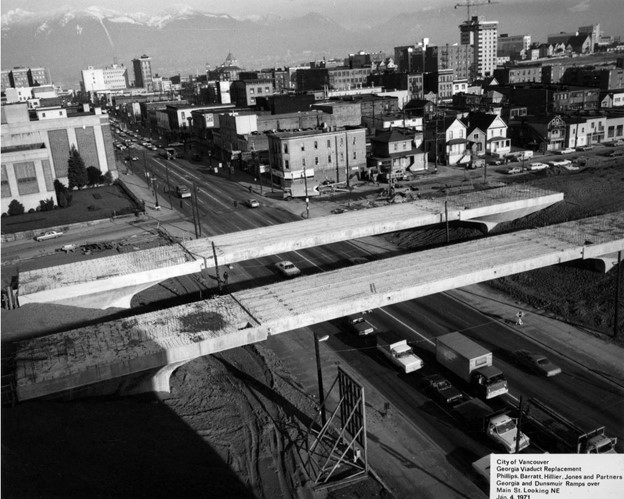

In the 1950s, the Canadian government rolled out an urban renewal program modelled on the United States. By 1956, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s urban renewal program enabled cities to access federal funds for slum removal after publishing thorough studies of “blighted” areas. The City of Vancouver’s 1957 redevelopment study did just that, identifying Hogan’s Alley as one of the worst areas and therefore “first priority” for removal. With the threat of eviction looming, these and the aforementioned discriminatory factors served to force Black residents out of East Vancouver. Hogan’s Alley was quickly demolished and erased from the cityscape. In its place today, there sits a small segment of an incomplete elevated highway system that was part of the urban renewal scheme.

Construction of the Georgia Viaduct through Hogan’s Alley in 1971. Photo credit: City of Vancouver Archives, CVA 216-1.23

In the 1960s, James Baldwin wrote, “Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.” This review of Canada’s lesser-known Black heritage offers a critical context from which to discuss our current social, economic and environmental crisis, the founding values and policy norms, the scaffolding from which our cities emerged. It also helps reveal the foundation on which our cultural heritage was built, centered and protected, one which maintains and entrenches white supremacy, poverty, misogyny, racism and ableism in our cities.

Consider this: when Canada’s urban areas were being established, where were people with disabilities? Tragically, they were systematically locked away in asylums and discarded from public life. The profound inaccessibility of buildings and public spaces is rarely considered when we assess whether they are worthy of heritage preservation. What is this telling us about how we value people with disabilities, when we enshrine areas to which they will never be able to have access?

Vie’s Chicken and Steaks in 1971 (house centre-left with dumptruck in front). Photo credit: Photo credit: City of Vancouver Archives, CVA 216-1.23

Or whose heritage do we celebrate and cherish? On the left is a photo of the heritage designated and celebrate Mole Hill district in Vancouver’s West End, which contains some 30 heritage listed properties. On the right is a photo of Vie’s Chicken & Steaks (209 Union Street) before it was demolished. It was a business operated by Vie and Bob Moore for more than 31 years, during which it was patronized by everyone from night shift workers to Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, Cab Calloway, and Sammy Davis Jr. The site where Vie’s once operated is now set for redevelopment, and a portion of the restaurant remains (207 Union Street). A City heritage review found the building did not have “heritage value,” but had a footnote that also said it should be recognized and commemorated for the historical significance to the Black community. This poses a particularly difficult task for the Black community when it has no control over the site nor the financial means to participate without dedicated government funds. Although the property owner has shown willingness to include participation of the Black community, they have no obligation, under existing requirements, to collaborate on the vision for the site or work with the community.

Vancouver is a city with both the wealthiest and most impoverished neighborhoods in Canada. Across the BC thousands of people are identified as experiencing homelessness Indigenous and racialized people being overwhelmingly overrepresented. As we see widening income inequality, scarcity of affordable housing, untreated physical and mental trauma leading to addictions, failed child welfare policies, inadequate supports for newcomers from marginalized cultures and ethnicities, and profoundly insufficient financial supports from people of all walks of life, particularly disabilities, the situation is only getting more critical. We can no longer plan and develop urban areas from the comfort of privilege, prioritizing those with power and advantage, valuing our colonial heritage in the built form, while devaluing the human life that sleeps in its doorways. “But what can I do about it?” you might be asking. After all, you have jobs to do businesses to run, and market demand to meet. My reply is that the magnitude of our converging crises is no longer debatable, delayable or avoidable.

The photo on the left was taken from my office on September 12 [2020] smoke from the wildfires in Washington and Oregon, put Vancouver as the city with the worst air quality in the world that day. The photo on the right was taken two years ago in the BC southern interior with flooding continuing to grow in their severity with each passing year. And I might also point to the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic and its ongoing impact on social, cultural, economic, and human wellness. All these things clearly demonstrate that our status quo is built on a foundation of inequities, making us ill-equipped to produce the swift and transformative changes we need in order to survive the challenges we face.

My suggestion is that we need to torch the status quo and replace it with systems, structures and norms premised on our shared humanity, acknowledging the evidence that our destinies are tied up with each other. This requires us to come to terms with the oppressive and discriminatory foundations on which our cities were built.

This first step will daylight how our cities privilege some and harm others. But of course, awareness alone is not enough, we must make significant moves on equity. These strategies can take many forms but must centre on the needs and voices of marginalized peoples and communities. We need to disrupt every part of the process – from how and by whom policy is designed, to the redistribution of benefits and resources – and not in a tokenistic way. This is by no means easy to do, especially in an urban environment that favors capital interests. But if your work teams and institutions include people with lived experience and deep analysis on how racism, ableism, and colonization show up in planning, architecture, development and Heritage Preservation, and they are given authority to educate and to lead, it will transform the quality of our of our work, our policies and our practice. It will also mean giving up reliance on technocratic planning methods or narrowly defined heritage standards, and understanding how such methods are entirely biased towards interests that are white male, able bodied, cisgendered and moneyed. These methods fall short on producing equitable cities.

Instead, I argue for a revolution of ideas of values, and unleashing our imaginations from being tethered to outdated and harmful systems. What if we measure results differently, establishing performance standards that advance human wellness, and the living standards of disadvantaged communities and people? We could we co-create with underrepresented communities, redistribute power, amplify voices that may challenge us or make us uncomfortable. We can tap into creativity and imagination that is rarely at the problem-solving table, or the traditional wisdom and knowledge that hold the key to the most complex problems we face. This is certainly true of the wisdom that is held by the world’s Indigenous communities, who know best how to support and restore the ecology that they have called home for millennia.

All of us here are a creative bunch and our potential to navigate this tumultuous time is possible if we shift our focus from preserving the heritage that centres on the humanity of an exclusive group of people (sometimes even representing a violent history of oppression) and hitch our imagination to the values of equity, compassion and shared humanity. May we get to work charting a way through the challenges that threaten our existence.

[1] Maynard, R. (2017) Policing Black lives: State violence in Canada from slavery to the present.