Exploring the hidden past

Urban exploration sometimes gets a bad rap. Media reports frequently associate it with trespassing, graffiti and vandalism, and this has helped drive a wedge between traditional heritage supporters and the urban exploration community.

Jonathan Castellino, a photographer and urban explorer from Toronto, helps break down these misconceptions, showing how heritage conservation and urban exploration are really two sides of the same coin. He underscored this point when he hosted a session on urban exploration at the 2016 National Trust Conference, Heritage Rising, in Hamilton, ON.

“No accurate reading of the practice includes any of these inherently destructive uses of space,” says Castellino. “Sure, there are people who do what ‘resembles’ urban exploration for purely exploitative reasons, but they would not be considered part of the community-proper.”

What isn’t always mentioned is the unique way in which these passionate photographers, adventure-seekers, and fans of history preserve historic buildings. Trespassing is not actually essential for urban exploration, and avid urban explorers are also opposed to damaging these properties. In fact, urban exploration is considered an activity that preserves history in a unique way. In a sense, urban explorers and traditional conservationists share core values.

“We maintain a relationship with place, and love these spaces just as they are – which includes a past and future, but most importantly a present-state,” says Castellino.

Fueled by curiosity, these rogue historians typically discover abandoned man-made structures through word of mouth, research, or websites such as the Urban Exploration Resource and Atlas Obscura. Popular types of structures include abandoned mental institutions, factories, hospitals, grain elevators, schools, storm drains, transit tunnels, and more. Urban explorers seek beautiful photography opportunities, thrills, and to experience history through a lens not offered in a classroom or textbook. They learn about historic places in their own personal and artistic way.

But when abandoned sites become very popular and are shared widely on the Internet, it can lead to an influx of visitors, which comes with a slew of problems such as an increase in vandalism and damage. Sometimes, a physical piece of the place is stolen.

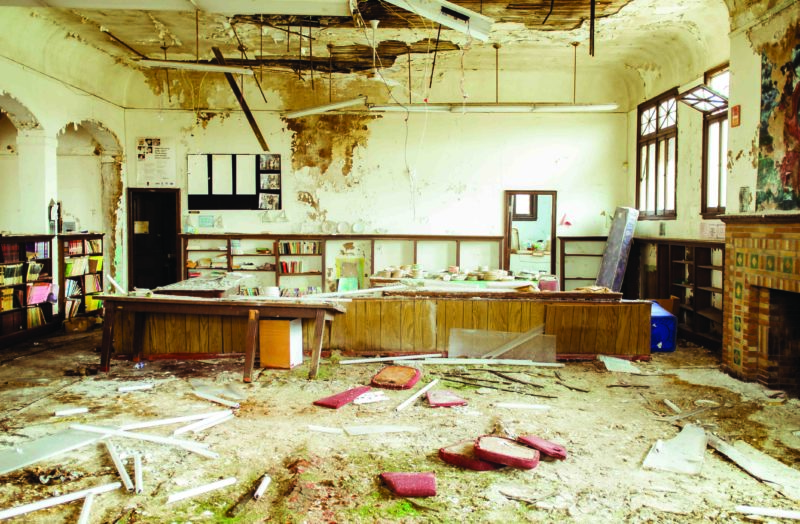

‘detachment.’ | abandoned midcentury modernist school in Etobicoke, ON. Photo by Jonathan Castellino.

Case in point: the Wallingford-Back Mine in Mulgrave-et-Derry, QC. This semi-natural former mine – first exploited by miners in 1924 to produce feldspar and quartz – was permanently closed in 1970 and soon became a natural treasure and local asset, popular with paddlers in the summer and skaters in the winter. But the abandoned mine began to attract an over-abundance of visitors in 2016 after it was featured in media stories as a “secret destination.” With no designated parking, bathrooms, or garbage cans, the site was ill-prepared for visitors, leading to complaints by local residents.

Access has now been blocked by large cinder blocks and fences in response to the large number of people visiting and despoiling the site. The mine, which was featured in the National Trust’s 2017 Top 10 Endangered Places List, is an unfortunate example of history, explored by too many people at once and by some who didn’t follow some of the key rules of urban exploration.

‘over.due.’ | abandoned John S. Gray (Carnegie) library in Detroit, Michigan. Photo by Jonathan Castellino.

“Most explorers have a personal code of ethics, harkening to the old adage of ‘take only photos, leave only footprints,’” says Castellino.

Photography plays a large role in urban exploration. For many, taking beautiful images is their main motivation for exploring – whether it be for personal satisfaction or to be seen by thousands of Instagram users. It’s also their main way of documenting and keeping abandoned historic places alive.

“A good photograph goes beyond what something looks like, and shows how it feels,” says Castellino. “So, in a way, urban exploration photography makes a memory of a building. A photograph is also an ‘image in time,’ so that it preserves a specific state and moment.”

These places are not static. As abandoned structures sit, materials deteriorate further or can even be taken over by nature, providing new photographic opportunities. “The role of the artist has always been to expand territory, to venture out into the unknown,” says Castellino. “Urban explorers do this in a very literal sense, shedding light on the hidden present.”

‘ghostly.’ | turbine hall at abandoned R.L. Hearn Generating Station in Toronto, ON. Photo by Jonathan Castellino.

One of the people he’s explored with is Tong Lam, a history professor at the University of Toronto. Lam’s recent book, Abandoned Futures: A Journey to the Posthuman World, unpacks our culture’s fascination with modern ruins, tracing the origins of this impulse back to the “ruin lust” of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. What distinguishes modern ruins from their forebears, Lam explains, is that they are not gently eroded ancient structures, but rather recently decommissioned factories, churches, and theatres – places that convey “a tragic melancholy and untimely death.” For Lam, the current interest in ruins is “partially a reaction to the uncertainties created by globalization, climate change, and runaway technological development… inviting us to reflect on betrayed dreams and unfulfilled promises.”

‘my.name.is.Agnes’ | abandoned St. Agnes Church (triptych) in Detroit, Michigan. Photo by Jonathan Castellino.

While largely ignored by the mainstream conservation community, it could be argued that urban explorers are preserving buildings by keeping their relevance alive through photographic documentation. They document places that are forgotten, unappreciated, and abandoned.