Church buildings repurposed to serve an aging population

I recently visited an old heritage church building in Brampton, ON that was wasting away from neglect, unoccupied and in the need of care and attention. While looking at it, I couldn’t get the comments of a French tour guide out of my mind when we visited Louis XIV’s Palais de Versailles located just outside Paris last Spring. I had asked her if the Palais was now owned by the French Government. She looked at me in amazement and said, “Mais non, Monsieur, I own it.” I suppose it was my turn to look surprised because she quickly added, “Oh, pardon! I mean, it is owned by the people of France. The Government only looks after it for us.”

The old church was not the Palais de Versailles but its history does go back to the original settlement period of the area in the 1850s. It was, in fact, the second structure to be built on the site. The first, a frame building, was outgrown by the original congregation and replaced by the present more permanent brick church in 1904. At the time, it was quoted in church records that, “great liberty was shown by the people in providing the means for the building.”

The old farming community has long since gone, but I felt that the original founders were intent on having a permanent place of worship on the site, but now it was on the verge of abandonment. Like the French tour guide, I felt that it was part of my heritage and believed there must surely be a use for the property that would serve the community better than just letting it be brought to the ground.

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated case. Many church properties across Canada and elsewhere – perhaps not as grandiose as the Palais de Versailles, but still significant heritage properties in their own right – are being written off due to demographic changes that resulted in declining congregations. Many have found other non-religious uses or were demolished to make way for condominiums and other forms of commercial enterprises.

Many former churches have been demolished. (Photo: Richard Longley)

We don’t have to look far to find growing needs in our communities for housing and associated services where unused church properties might serve a useful purpose without being demolished. Statistics Canada, for example, recently reported that for the first time since Confederation we experienced the greatest increase in the number of older residents in Canada. This is due to a historic increase in the number of people over 65 – a jump of 20 per cent since 2011, and this is just the beginning. By 2031, they project that 23 per cent of all Canadians will be seniors. These figures are hard to ignore, and should alert everyone to the growing needs of this important segment of our community.

An interesting example of how one community dealt with this problem can be found in Farragut, a suburb of Knoxville, Tennessee. I had an opportunity to be in Farragut recently and met with David Smoak, the town administrator, who is credited with bringing about a successful alternate use for a large vacant church property in that community.

The Faith Lutheran Church of Farragut moved from their 35,000 sq ft., five-acre site to a larger church property because of an expanding congregation and the property was put on the market for sale some four years ago. David Smoak saw a real opportunity to put the former Lutheran Church to another use that would greatly benefit the community. He was aware that the Town had been looking for a site for a community centre, so he worked with all parties, including the church and county administration to have them agree on a purchase and sale of the unused property and share in the project to rehabilitate it into a community and senior centre for the benefit of all the citizens of both the town and county. As the local newspaper put it, it was “a win-win for all.”

Former Faith Lutheran Church, Farragut, Tennessee. (Photo: Robert B. Hulley)

Geriatrician Dr. William H. Thomas, an international expert on elder care, set out to redesign retirement and nursing homes “from scratch” with the goal of personalizing elder care by providing residents with more privacy and control over their lives. I had an opportunity to visit one of the facilities and immediately saw how many unused church properties could be adaptively reused to accommodate most of his theories while continuing to serve declining congregations. It seemed to have the makings of another win-win situation.

Surveys have shown that many elders wish to remain in their homes for as long as possible. Of course, for a variety of physical and medical reasons this is not always possible, but even for those who are able, there are many risk factors involved in living alone. Some experience isolation due to a decreased social network, infrequent participation in activities with others, bereavement and lack of companionship which leads to a feeling of abandonment and loneliness. Research demonstrates a strong relationship between loneliness and poor health, including diminishing immune functions, depression and cognitive decline.

Dr. Thomas believes that many people see existing retirement facilities as grim places where residents often feel out of place and living in a regimented environment. Instead of an institutional setting, he suggests providing a homelike atmosphere for seniors by providing shared housing units for those who are physically fit and mentally able to do so. His basic premise is that, “older people will thrive in a home if it resembles living in one’s own house. The secret is to give residents more privacy and more control over their lives.”

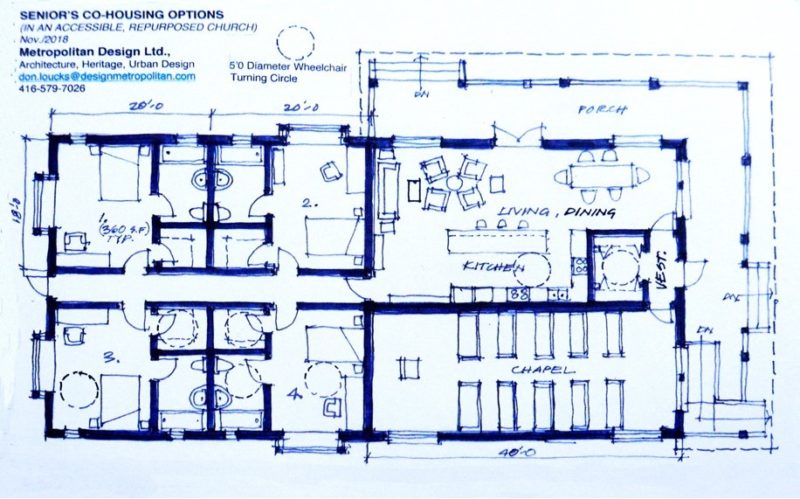

Churches facing the possibility of closing can more than meet this need if their interior space can be subdivided into individual bed-sitting-rooms with adjoining private bathrooms and a communal kitchen and common room. Ownership would remain with the church and leasing the units would provide a much-needed source of revenue for upkeep, maintenance and administrative costs.

An important part of this remodeling would be to convert part of the existing church into a chapel. This could accommodate the remaining members of the congregation and any important vestiges of the former church such as memorial plaques or memorabilia including pews, heritage stained glass windows, and a brief history of the former church’s contribution to the community. In addition, in this ever-changing communications environment it’s not hard to imagine the chapel being equipped with a closed-circuit video feed to carry sermons from associated churches in the area and possibly from larger destination churches on special occasions. (See concept plan for a small church’s re-design below)

Floor Plan by, Don Loucks, Architect, who specializes in eldercare design. (Floor layouts would vary with the shape and size of the individual church property.)

This would allow churches to maintain a presence in the community and be responsible for the administration of property. Looking to the future, neighbourhood demographics are continually shifting and evolving. While a particular church’s attendance may be on the decline at the moment, experience has shown that things do indeed change and reverse themselves. In these circumstances the decision to sell a church property may prove to have been premature over the long haul and invite costly remedial action to restore its place in the community later.

Church properties are unique; they are not ordinary buildings, they were specially built for and by the people to meet a community’s religious needs. However, should circumstances change, and they are no longer fully needed for their original purpose, their large open interior spaces give them meaning and value for adaptive reuse as eldercare facilities. In this capacity, they can still play an important and vital role in the community by providing shared living accommodation for seniors while continuing to serve their remaining partitioner on a limited basis.