A Culture of Inertia

A story that profoundly touched me was told to us (siblings) by our mother, a childhood memory and one which would have been very emotional and *culturally foreign.

My mother’s and father’s childhoods were spent on the land much like the old Inuit. I imagine it was a bit of a confusing time because while they lived in tents and igluit, the others (RCMP, Roman Catholic Church, Government Agents, and the Hudson’s Bay Company) had “homes” of wooden structures. Imagine a village of igloos interspersed with wooden homes: a near permanent and new presence, a new language, changing rules of survival, an either or situation. I call this period the “transition” years. These transition years were brief but a time of great emotional and cultural distress.

It was during this time of transition and distress in the 1950s that several policies were developed, designed to begin the process of “managing the Inuit problem.” Part of this dialogue was about placing Inuit into permanent settlements, one solution and consequent policy was the education policy or the residential school policy (the assimilation policy).

This same policy was adopted/adapted and enforced to begin to educate Inuit children; many were forcibly taken from their families/camps and placed in residential schools.

As we hear through many similar stories, many Inuit children were simply “picked up” and taken from their respective camps by church and government agents and delivered to churches and/or residential schools to “begin” their education. My mother’s story is much the same: late one summer while with her Grandmother Tahiuq, she was simply picked up (along with her brother, our Uncle Evano), taken from her Grandmother and camp at Tingmiaqtalik and brought to a mission house at the mouth of the Maguse River (Padlei) along the Hudson Bay coast (not far from what is now Arviat).

My mother recalls spending several days at this school but she did not want to be there so one night she got away and walked for three nights and four days to get back to her Grandmother and to return to her camp.

I often wonder what it must have felt like for my mother and especially for her Grandmother Tahiuq to be forcibly separated from each other without really understanding when and if you will see each other again, as permission was not really asked or granted.

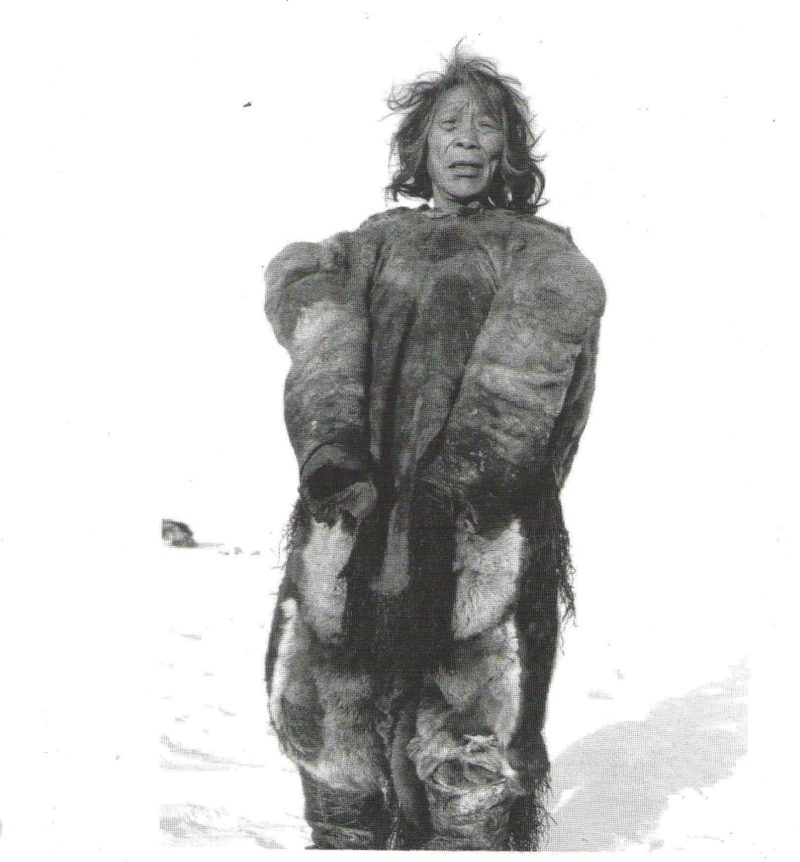

The emotion I always come back to when I think of that period is best described by one inuktitut word, ilira ᐃᓕᕋ, the word ilira encompasses many feelings at once: inferiority, fear, inadequacy – all of these emotions come together, fuse so as to create a sense of profound emotional discombobulation, our grandmothers and grandfathers must have been so ilirasuktuq (ᐃᓕᕋᓱᒃᑐᖅ) so as to become profoundly uncertain and therefore helpless. We need to understand this period through the lens of the emotions that would have overcome this generation. To understand this period of distress may shed some light on its consequent culture created by this time, the methods of transition and communication, the culture of inertia.

The love between my mother and her grandmother was so strong that my mother knew once she returned to her Grandmother she would be safe. This love was given to her during her formative years and this generation was the last to live their formative years in traditional culture. I asked her during a chat recently if she had ever felt ilirasuk and she said she never has whereas I have pursued my career almost always feeling ilirasuk.

Photo: Dr. Susan Aglukark’s mother’s grandmother, Tahiuq.