Endangered Places List 2020 – A Year in Review

Since 2003, the National Trust’s Endangered Places List has shone a national spotlight on heritage places at risk across Canada – from places of faith to Indigenous cultural landscapes, community landmarks to vernacular homes. In 2020, the List’s usual spring release date was sideswiped by COVID-19, which exacerbated existing heritage challenges and pulled the sector’s attention to new pressing needs. As 2020 draws to a close, we’re sharing a few of the issues that occupied us this year – and signaling new directions for the Endangered Places List as a powerful tool in the advocacy toolkit.

Places of Faith

National Trust research shows that a third of Canada’s 27,000 faith buildings – more than 9,000 – could close permanently within the next decade. The 2020 pandemic has seen faith buildings shuttered to services across the country, declining income, and accelerated permanent closures. This surge is not just a crisis for built heritage, but the loss of the essential community uses they enable. A 2020 report supported by the National Trust, “No Space for Community: The Value of Faith Buildings and the Effect of Their Loss in Ontario” measures faith building usage and how closures could impact the wide range of not-for-profit services and community groups that rely on them.

“The current crisis has reminded us of the importance of not-for-profit landowners,” says Kendra Fry, project lead at Faith and Common Good. “38% of survey respondents indicated that they were paying nothing for their spaces in faith buildings, and a large group report paying minimal amounts. These important not-for-profit and community groups cannot afford commercial spaces. If the faith buildings close, what will happen to these groups and the people they bring together?”

In Church Point, Nova Scotia, Église Sainte-Marie towers over the landscape. Erected in 1903-1905 by 1,500 local volunteers, it is the largest wooden church in North America (taller than the Statue of Liberty!) with each of the 70 foot columns in its nave hewn from local trees. With a repair deficit of $3,000,000, the local Catholic Diocese has given local volunteers until 2021 to raise the funds, or demolition will follow.

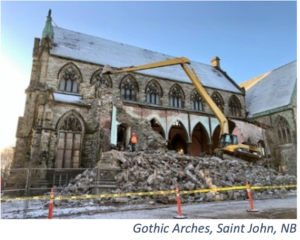

Across the Bay of Fundy in New Brunswick, the backhoe came for the Union Street Baptist Church in St. Stephen this past year, as well as one of the largest churches in Saint John: Gothic Arches (1877) with its soaring hammer-beam roof and hand quarried stone was reduced to rubble. In Battleford, Saskatchewan, the end is near for St. Vital Church, the oldest Roman Catholic church in the province and directly connected with the North West Resistance of 1885.

Heritage Sites Open to the Public and Community Spaces

The 2020 pandemic lockdowns have brought extreme financial and human resource pressure to Canada’s heritage sites and museums. Many sites could not open to the public this past summer, and lost ticket revenue and donations pose an existential crisis. A Heritage BC “Heritage Health Check” survey alarmingly reported that 32.5% of BC heritage sites may never fully recover, with many closed for good. Further compounding the crisis is the erosion of the community volunteer base or seniors that undergird many heritage sites. The #ShovelReadyHeritage campaign – championed by Canada’s heritage sector and led by the National Trust – has sought federal pandemic stimulus funding to address the deferred maintenance at many of the sites: over $356,000,000 in potential work was identified at over 200 sites. In response, the Province of BC announced a commitment of nearly $20 million in funding for heritage projects via its Community Economic Recovery Infrastructure Program, and it is hoped that additional funds will be secured for other jurisdictions in the coming period.

Commercial Heritage Places

Canada’s traditional Main Streets have seen heavy re-development pressure in recent years, resulting in widespread demolition in places like Toronto, and drawing action from the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario. The pandemic has sharpened these threats. Heritage Vancouver’s 2020 Top Ten Watch List, for instance, singled out the current dire risks to neighbourhood businesses. The Canadian Urban Institute through its Bring Back Main Streets Initiative (of which National Trust is a partner) has brought attention and innovative solutions to heritage commercial corridors, through tools like the Main Street Design Challenge Playbook.

At the same time, the absence of funding for large heritage projects is a mounting challenge and the need for federal incentives for heritage rehabilitation, more acute. A few examples: The pandemic-accelerated closure of Winnipeg’s landmark Hudson’s Bay Building creates tremendous urgency to find an adaptive reuse for this keystone downtown building. The Cyclorama of Jerusalem in Ste-Anne-de-Beaupré, recognized by the Quebec Minister of Culture, is still for sale and deteriorating. In Edmonton, the historic Hangar 11 (included in Trust’s 2017 Endangered List) continues to languish, with stabilization costs of $20 million, while the Minchau Blacksmith Shop, which made the 2018 Endangered List, was demolished in September – a victim of spot zoning and limited funding.

Climate change is at the top of the national agenda. Rapidly accelerating the reuse of Canada heritage and older buildings offers one of the quickest ways to help achieve Canada’s climate change targets. Yet Canada’s real estate development industry and marketplace is geared towards new construction, which carries a heavier environmental toll than building reuse. The National Trust’s report Making Reuse the New Normal: Accelerating the Reuse and Retrofit of Canada’s Built Environment released in November, itemized the barriers to reuse and identified recommended solutions.

Residential Heritage Places

The need to densify older neighbourhoods, limit sprawl, and reduce our carbon footprint is broadly recognized. High-profile struggles in 2020 around two heritage houses foreground the need for strong civic leadership when it comes to successfully weaving new and old.

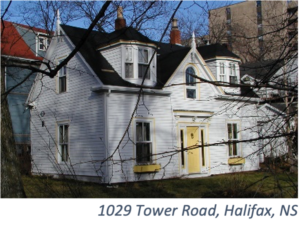

When a policy change stripped heritage protection from 514 Wellington Crescent in Winnipeg in 2016, a developer immediately purchased the property intent on replacing it with condominiums. Despite a multi-year advocacy campaign that galvanized the city, the house became a demolition spectacle in November. Meanwhile in Halifax, the Georgian wooden cottage at 1029 Tower Road (Endangered Places 2018) looked set to meet a similar fate. The developer, municipality, and heritage groups compromised by repositioning the house on the lot and adding additional density.

Other cities have been equally creative: The City of Calgary voted to create pathbreaking new incentives to spur the retention of housing stock in character areas. The District of West Vancouver took the unusual step of subdividing a property and allowing short-term rentals to ensure the future of a mid-century home designed by Ron Thom. Incentives like these could have helped tip the balance for Reid House (1760) in Avonport, Nova Scotia, a provincially designated illegally torn down in December. The Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia is calling for an inquiry and levying provincial law’s maximum fine of $250,000.

Federally Owned and Regulated Heritage Places

In December 2019, a singular heritage task appeared in the PM’s mandate letter for the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to, “Work with the Minister of Canadian Heritage to provide clearer direction on how national heritage places should be designated and preserved, and to develop comprehensive legislation on federally owned heritage places.”

2020 has been full of examples that point to the need for this work: The federally designated railway station at Hornepayne, Ontario was demolished, and many more, despite their status under the federal Heritage Railway Stations ‘Protection’ Act, are at risk, including the station at White River, Ontario, Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, and Prince Rupert, BC. No one is charged with monitoring or reporting what’s happening with them. More recently, the impending demolition of the historic Alexandra Bridge in Ottawa was announced as a fait accompli, with the public invited only to comment on how it might be commemorated after it is gone. And who can forget the battle for Ottawa’s Chateau Laurier Hotel, a site that despite national significance and a federal designation was headed for a shocking addition, were it not for a national advocacy campaign ably led by Heritage Ottawa.

See the National Trust’s recommendations for the Minister’s federal legislation work here.

Hornepayne Railway Station, Hornepayne, ON

Places and Land Valued by Indigenous Peoples – New Directions

As Karen Aird and Gretchen Fox explain in their 2020 report, Indigenous Living Heritage in Canada, “Indigenous Peoples see cultural heritage as the dynamic interweaving of tangible and intangible heritage, language, traditional knowledge, and spirituality.” While the Endangered Places List has included some Indigenous heritage places in the past, we know that the List, and indeed conventional Western heritage systems writ large, need some fundamental re-thinking if they are to be inclusive, appropriate and effective – and further, that Indigenous heritage preservation efforts need to designed and led by Indigenous Peoples. So, we are delighted to announce our latest undertaking with the Indigenous Heritage Circle, which includes co-hiring Raven Boyer to lead a fundamental re-thinking of the Endangered Places List from an Indigenous perspective. We are delighted to welcome Raven, who is working remotely from the traditional unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik and Mi’kmaq Peoples, in Moncton, New Brunswick.

National Trust Endangered Places List in 2021

Next year, in addition to making the List more meaningful for Indigenous heritage places, the Trust will use this proven tool in new ways: Instead of a single annual call for nominations followed by a media release of all 10 places, the National Trust will now be accepting nominations to its Endangered Places List throughout the year – and we’ll be naming places to the List in real time, at moments throughout the year that best serve the needs of each particular case. We’ll also complement the Endangered Places Tool Kit with a new webinar that shares the best advocacy strategies we’ve seen working on the ground.

Onward and upward, heritage advocates!